Only 18 per cent of our rural population have access to three basics of 21st century living: drinking water in their homes, sanitation and electricity; and a fifth do not have access to any of these, says Rahul Jacob.

As trade talks in Geneva ground to their conclusion last week, hardly a day went by without one senior Indian official or the other reaffirming the country’s commitment to its poor farmers.

On Tuesday, it was the turn of Finance Minister Arun Jaitley to explain the India versus the rest of the world position, this time to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), that the government was “determined to resist and block all anti-Indian farmer moves by WTO (World Trade Organization) and other agencies”.

As so with so much of what this government says and does, it sometimes seems as if the Congress party is using ventriloquism to broadcast such platitudes through the mouths of BJP stalwarts.

To the uninitiated on “peace clauses”, the Indian position in Geneva sounded eerily familiar to Congress’ commerce minister Anand Sharma’s arguments in Bali in December.

Both parties are in favour of high support prices that primarily benefit rich farmers to procure grain that is then left to rot or be pecked at by pigeons because our warehousing is inadequate - do a Google search for a recent Reuters photo essay on India’s granaries to see the results.

...

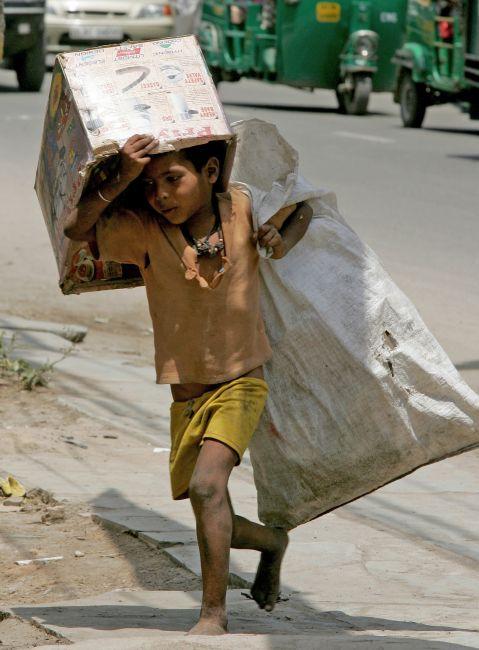

But, in recent years, as the benefits of the Green Revolution have run their course, few organisations have seemed more anti-farmer than the Indian government. The preference for subsidies and hand-outs at the expense of investment in rural infrastructure has left our villages even further behind the rest of India and the world.

Consider the credentials of our pro-farmer governments: almost half our rural households lack electricity connections.

Most of the other half have such unreliable supply that those who are able to get the kerosene sold at a subsidised price that does not make its way on to the black market or to Nepal use it for lighting - only one per cent of kerosene in rural India is used for cooking.

Only 18 per cent of our rural population have access to three basics of 21st century living: drinking water in their homes, sanitation and electricity; and a fifth do not have access to any of these.

A staggering 70 per cent don’t have access to proper toilets. Nearly all continue to cook with cow dung and wood in enclosed spaces, leading to respiratory diseases.

...

As the IDFC’s rural development report, from which these grim statistics are drawn, observes, “Government spending on infrastructure has a more significant and lasting impact on poverty reduction than government outlay on fuel, food and other subsidies.”

This point has been made so many times before that one is left baffled by the political calculus that prompts successive governments to carry on with business as usual.

The release last month of the Human Development Index, which showed that countries like Bangladesh, Cambodia and Palestine are making more rapid progress than India on yardsticks like the number of years children spend in school and infant mortality is humbling. Life expectancy in Bangladesh is now up to 70.7; India’s is 66.4 years.

Their kids spend almost a year longer in school than the 4.4 years on average that Indian children do. Cambodia’s life expectancy is 71.9 and the average number of years in school is 5.8.

In the 1970s, Cambodia under Pol Pot’s reign of terror and Bangladesh at the time of its independence were widely regarded as basket cases. What does it say about India’s governance that they have surpassed us on many indicators of health and well-being?

...

There are many problems and many solutions; we will, in the guise of caring, be arguing about them for the next few decades at least.

But a research paper put out in March entitled “Sanitation and health externalities: Resolving the Muslim mortality paradox” presents both problem and solution so succinctly that it must be pushed to the top of the government’s priority list.

The paper, written by Michael Geruso and Dean Spears, looks at the puzzle of why Muslims in India have “significantly lower child mortality rates than Hindus”, despite being, by and large, less well educated and less well off.

The “paradox” is easily explained: Hindus are 40 per cent more likely to defecate in fields and near the streets where they live than Muslims. Because this leads to the spread of faecal pathogens, usually through water, that make infants and children ill, there is an 18 per cent child mortality gap between Hindus and Muslims.

“At any level of asset wealth or consumption, Muslims are 15 to 20 percentage points more likely to use latrines and toilets,” the authors write.

Parenthetically, the vast numbers of crude toilets built in Bangladesh in recent years, as well as the efficient distribution of rehydration salts to mothers with babies suffering from diarrhoea, has played a major role in bringing down child mortality there, despite Bangladesh, like Cambodia, having a per capita income that is about half India’s.

...

Mahatma Gandhi famously brought the issue of open defecation to public attention in the 1920s. Narendra Modi admirably said that toilets were more important than temples during his election campaign.

The government’s target of 2019 for cleaning up the country and ensuring everyone has access to toilets is a brilliant idea, but it will need real commitment and ingenuity to build that many toilets and make up for the lack of water in many parts of rural India by converting them, for example, to biogas plants.

There is also a social preference among Hindu men in rural India to defecate in the open even when there are toilets. Who better than the inspirational leader of a proud Hindu party to repeatedly remind his countrymen that this is a medieval practice and that we must learn from our poor Muslim brethren on this score?

As we turn 67 on August 15, let us not be distracted by coveting Japan’s bullet trains nor the pre-fab wafer plants that China has built. Let Mr Modi direct his gifted oratory, as Mahatma Gandhi did, at ridding us of this plague.

Let us learn from Bangladesh - as well as Beijing. Starting with our paucity of toilets and clean drinking water, we are a mediocre nation with much to be modest about. It is time our leaders faced up to this fact.