Can we find fault with RBI for not intervening enough in the market? Actually no, say some experts. A correction in rupee was long overdue.

The recent sharp rupee depreciation has brought in question the role of the Reserve Bank of India, and whether it could have done more to prevent such a slide.

Some experts in the markets see the rupee slide as a sign of an impending crisis, whereas others feel letting the rupee depreciate is just the right thing to do as a correction was long overdue.

The rupee was at the level of 68.61 a dollar at the beginning of August and, by its end, it was at 71. It was at 63.66 a dollar at the start of the calendar year.

“It is futile to predict the near-term exchange rate," wrote HDFC Bank chief economist Abheek Barua in a note.

“On the domestic front, the intensity of RBI’s intervention has dissipated.

"While there is complete lack of communication from the RBI, comments of officials from the government and quasi-government agencies appear to give the impression that they support fall in the rupee’s value in the interests of competitiveness,” Barua wrote, advocating that to arrest the slide, the government and the RBI must change their minds, and see the fall as a 'crisis' that needs to be tackled.

Barua is not far from the general sentiment in the market.

Many currency traders, anonymously, are blaming the RBI for the rupee slide.

The central bank is widely seen as an entity too eager to not let the foreign exchange reserves dip below $400 billion, at the cost of the exchange rate.

“RBI says it is out there to protect volatility, and not defend a level. If this is not volatility, then what is? It has neither protected volatility, nor has it protected a level," said a disgruntled markets head of a bank.

Apart from the geopolitical factors such as US tariffs on China and even on India, and sanctions on Iran, in the domestic market, too, a couple of factors had built up enormous pressure on the rupee.

A part of it is RBI's own doing. What made matters complicated was the huge and unexpected dollar demand in the month end. There were heavy, defence-related dollar purchases. And, demand was high because of the oil bill payment.

On top of that, RBI's forwards came for due in the month end. A bulk of $2.2 billion, due in the month end, was because of RBI's forwards operations, say currency dealers.

In the past, RBI continuously intervened in the forwards market, instead of the spot market, so that liquidity is not squeezed out.

RBI did that by buying dollars at a future date (forwards), instead of the spot market. It therefore intervened when portfolio flows were coming in unabated.

However, the issue here is that the forwards have to square off at some point in the spot market. August-end saw a massive pressure on that account.

The exact data will be known after two months, as it comes with a lag.

So, for example, till December, the RBI had built up a forwards position of $31 billion in order to intervene in the currency market. According to latest data, the outstanding forwards position in June was at $10.7 billion.

However, RBI could have smoothed the impact by supplying dollars in the spot market. But the central bank did not do much.

There can be two types of interventions in the market. One that is gradual -- to let a level remain protected till enough natural pressures build up to dictate a new level.

Or, there could be heavy intervention, as is the case in Japan, which triggers margin calls on speculators and nobody dares to take a contra position to pressurise the currency.

The RBI generally takes the first approach as the size of the speculators, mainly banks, is not much.

But in the latest episode, currency dealers said, RBI was not found even doing gradual intervention.

But can we find fault with RBI for not intervening enough in the market? Actually no, say some experts. A correction in rupee was long overdue.

"The rupee had not really depreciated between 2014 and 2017, based on fundamentals such as inflation differentials (with developed markets), current account deficit (CAD) etc.

"If you have a wide CAD, the natural market-based correcting factor is currency weakness, so that the import demand dampens, and exports at the margin become more competitive," said Hitendra Dave, head of global banking and markets for HSBC India, supporting RBI’s largely hands-off approach.

Based on real effective exchange rate (REER) vis-à-vis 36 trading partners, rupee should be at 73.87 a dollar. RBI's intervention strategy could have been guided by this.

"In 2014 to 2017, the excess supply of dollars was largely portfolio-driven, so it was right for the RBI to soak it up.

"But now the excess demand is not due to portfolio withdrawals, but owing to widening external deficit, and thus the intervention strategy needs to be different, which is what we are seeing," Dave said.

Agrees Madan Sabnavis, chief economist of CARE Ratings.

"It is a good thing that the RBI is not actively intervening. By aggressive intervention, RBI would have brought down the reserves when the world is seeing some uncertainty, but that would have supported the exchange rate for a few trading sessions only," said Sabnavis, adding the volatility could continue for the whole of September, before things start settling down.

One major factor here is that the oil prices could correct, as supply is increasing after major oil producing nations and Iraq are pumping up their production to compensate for the Iran sanctions.

But most in the market expect that the central bank will not allow the rupee to slide much from the present level as that would send a really wrong signal about the country to overseas investors.

In that case, either the foreign exchange reserves dip below $400 billion, or Indian banks could be told to raise dollars abroad aggressively to aid trade finance, or if needed compensate for the reserves spent in intervening.

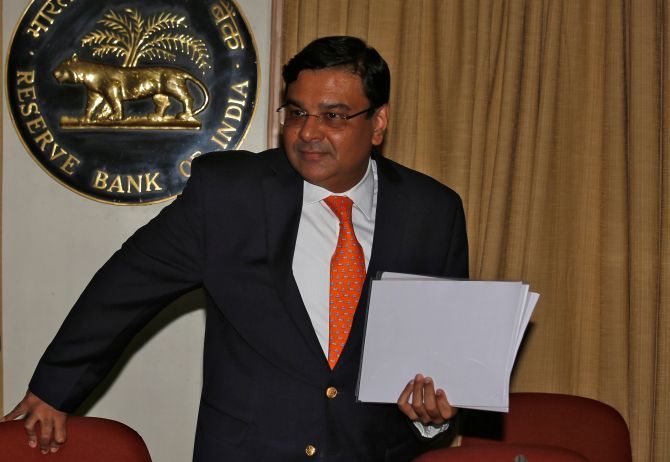

Photograph: Francis Mascarenhas/Reuters