Mitron probably would have continued with the free run for quite some time, had it not come to light that the source code of the app was actually developed by a Pakistani developer, reports Neha Alawadhi.

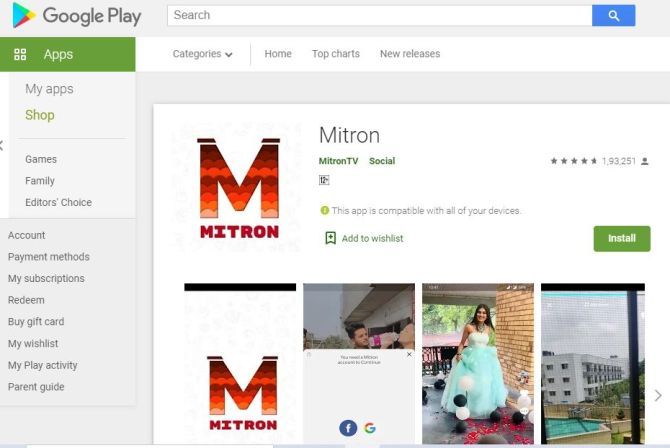

Several attempts have been made in the past to bring in the patriotic or swadeshi angle to sell products, solutions or services in India, but few have seen the kind of success that the little-over-a-month-old short video app, Mitron, saw, before it was finally taken down from the Google Play Store on Tuesday.

With over five million downloads since its launch in April, the developers or owners of the app managed to leverage two things quite clearly -- naming the app Mitron, a term made popular by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is perceived as a champion of nationalism, and the need to find an alternative to Chinese TikTok.

Though it was reported that the team behind the app was led by an IITian named Shivank Aggarwal, subsequent attempts to trace the said person drew a blank. The team went by the name of ShopKiller and maintained that it was working in stealth mode.

Google confirmed the suspension of the app from its Play Store.

The Google Play Store has a "Spam and Minimum Functionality Policy" and can take down apps, among other things, for repetitive content. Examples of violations include "Copying content from other apps without adding any original content or value" and "Creating multiple apps with highly similar functionality, content, and user experience".

Mitron probably would have continued with the free run for quite some time, had it not come to light that the source code of the app was actually developed by a Pakistani developer.

The entity called ShopKiller had bought the source code of the app from a Pakistan-based firm called Qboxus. The sale took place on CodeCanyon, a kind of marketplace for buying and selling of scripts, entire apps, and components for a variety of languages and frameworks.

As a result, Mitron was branded a Pakistani app, killing some of the initial euphoria around its rise.

The developer community however says that buying source codes of popular apps is quite a common practice, everywhere in the world.

"There are at least 500 developers selling source codes for popular apps like Instagram, Tinder, Uber etc. If just the source code was enough, anyone could’ve built these apps,” said Deepak Abbot, founder of financial technology firm Flat White Capital.

What needs to be commended, Abbot says, is the hacker mindset of the team that developed Mitron.

“They used the right name, identified the right opportunity at the right time and used the right kind of WhatsApp marketing and got as many downloads as they did in such a short period of time."

The growing sentiment against Chinese apps, leading to uninstall campaigns on social media platforms, coupled with Prime Minister Narendra Modi's call to be "Vocal for Local," fuelled the growth of Mitron to a large extent.

Qboxus' TicTic -- Android media app for creating and sharing short videos v2.5 -- available on CodeCanyon for $34 (about Rs 2,570) is one of the bestselling app codes this week. The developer also sells an Android code for Hashgram, a clone of Instagram ($19), Binder, a dating app like Tinder ($44), and several other ready-to-use codes for e-commerce and food ordering websites.

However, the popularity that Mitron managed to gain in a short span is commendable.

For example, there were at least 14 other apps available on Google Play Store as of Monday evening, whose names were quite similar to Mitron with very minor variation, offering similar or different kinds of services.

- Growing sentiment against Chinese apps fueled growth of TikTok clone Mitron

- Reached over 5 million downloads in less than a month

- Mitron team worked in stealth mode, no clarity on who owns or runs it

- Pakistani firm claims that app's source code was bought from them for $34 on code marketplace CodeCanyon

- Study found many clone apps contain malware and poor data usage policies

- Google Play Store suspends Mitron for policy violation

Given the fast popularity of the app, many have tried to clone the clone. However, experts believe that clone apps do not have well-defined data usage and privacy policies which puts the users under risk.

“It is becoming increasingly common for the source code of applications to be bought on the cheap, be slightly modified, and then re-published on app stores where people behind these apps are able to turn-over revenue through ads/in-app purchases. To most users, these applications are indistinguishable from those developed by larger companies, and that is where the problem lies. An already existing trust deficit is widened when unmaintained applications are mass-produced in such a fashion," said Karan Saini, a security researcher.

Saini likened the "fast apps" industry to the fast fashion industry, which doesn't necessarily hurt the consumer, but has the potential to do so if the app collects sensitive user data. For instance, a clone of a dating app could potentially expose users' personal data to unscrupulous elements.

A 2019 study conducted by the University of Sydney and Data61-CSIRO, investigated over one million Google Play apps and discovered 2,040 potential counterfeit apps. Many of the fake apps impersonated highly popular apps and contained malware, with popular games such as Temple Run, Free Flow, and Hill Climb Racing being the most commonly counterfeited.

The study also found that several counterfeit apps request dangerous data access permissions despite not containing any known malware.

The Mitron app did, at some point last week, put up a simple, single-page privacy policy. An email sent to ShopKiller e-commerce did not elicit any response.

As Abbot said, the shelf life of a lot of these apps, however, is not necessarily long. "The app (Mitron) may fade away in a couple of months, given the engineering might of TikTok, but what Mitron has achieved riding on the anti-Chinese app sentiment is commendable," added Abbot.