By setting up massive capacities in a limited market against entrenched competition, founder Bhavish Aggarwal has his work cut out proving the sceptics wrong, says Surajeet Das Gupta.

His key potential rival, a domestic two-wheeler with a global presence, dismisses the plan as “outrageous” and impossible to comment on.

Others say it is just a game to up Ola Electric’s valuation, because its flagship ride-hailing business has faced a tough year due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Ola Cabs’ valuation was recently downgraded by one of its investors, US-based Vanguard Group).

But that does not deter founder Bhavish Aggarwal from doing what he knows best — disrupt the market — with an ambitious plan to shake up the internal combustion engine-dominated two-wheeler market over which Hero, Bajaj, TVS and Honda preside.

Aggarwal announced that in the first phase he is investing Rs 2,400 crore and putting up an electric two-wheeler plant with a capacity to churn out 10 million a year by 2022.

He is hoping the first phase of the plant with a capacity of two million e-scooters will be up and running by June (construction started in February).

He is not ready to offer details about the e-scooter but is certain customers will lap it up because of its price-value combination.

And he will also export to Europe, which is a big e-cycle market, and Australia.

“We understand the scepticism from rivals,” said a member of the Ola Electric leadership team.

“But in the past 40 years, one hasn’t seen any significant technological innovation in India in scooters at all — imagine, the carburettor is the norm.

"Customers are ready for a superior tech-driven product at competitive prices. And we are building scale.

"The inflexion point has come and (the time for) linear organic growth is over.”

True, India is far behind China, which sells 28 million e-two wheelers a year, and Europe (about four million). India sells just 150,000 e- two-wheelers, most of them running at speeds of less than 25 kmph.

There have been concerns that India might lose the EV race.

But manufacturers furiously resisted Niti Aayog’s move to fix 2025 as the deadline for all two-wheelers with engine power of up to 125 cc to go electric.

As a tech services company, Ola has never been in hardcore manufacturing.

And unlike in ride hailing, which is a two-player market (Uber is the only other competitor), in two-wheelers it faces many entrenched players.

But most of all, rivals say Ola’s targets are out of sync with most, even ambitious, projections.

For instance, McKinsey has projected that the Indian e-two-wheeler market will hit 4.5-5 million in FY 2025, accounting for 25-30 per cent of the total market (including internal combustion engine or ICE products) and nine million by FY30 (around 40 per cent of the total market).

Ola is, however, putting up capacity next year that is equivalent to the entire market for e-two wheelers in 2030.

Also, after four decades, India is the world’s largest ICE two-wheeler market with annual production pegged at 20 million.

Ola is creating capacity that will be equivalent to half this number.

It clearly expects a dramatic rather than a gradual shift from ICE to e-two-wheelers in a few years.

Legacy players don’t see it the same way and neither does the government.

The 2019 FAME 2 policy (that offers consumers subsidies to buy e-two-wheelers) had assumed about one million high-speed two-wheelers on roads by March 2022.

The reality on the ground is that only 257,000 high-speed scooters (above 42-45 kmph) were sold in 2020.

So can a tech company that is taking its first steps in manufacturing disrupt the market?

It all started in 2017 when Ola experimented in Nagpur with a range of electric vehicles (EVs) to electrify over 10,000 vehicles of its own ride-sharing fleet.

In 2019 Ola Electric catapulted into the Unicorn list when Softbank made a big bet by investing $250 million.

Keeping company were Kia and Hyundai, which also invested money and have been pursuing aggressive EV plans for passenger cars.

Ola Electric executives say they are focusing on the urban commuter market (not so much B2B, which includes e-commerce delivery).

The problem, they say, was the price tag, more than double that of an ICE offering.

Scale was the standard solution to lowering costs.

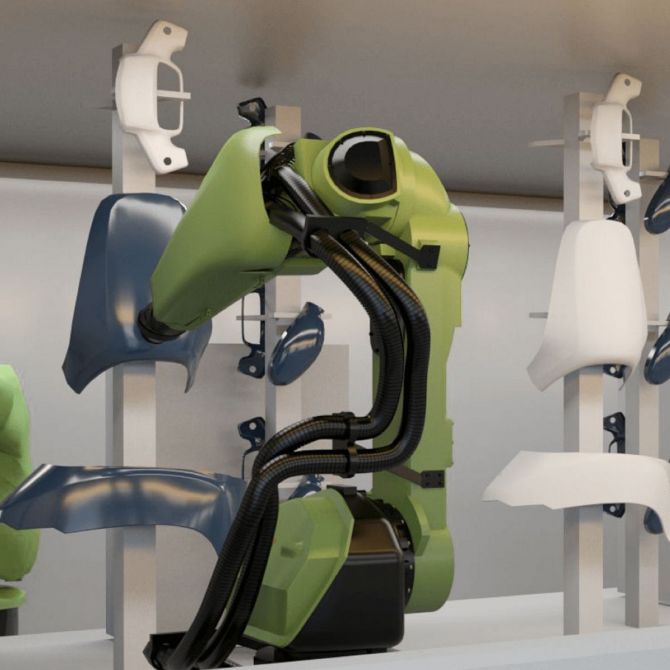

So Ola is building the world’s largest scooter factory in one site, 90 per cent of the components are co-located.

It is making all the core parts such as battery and motors, putting localisation levels at 90 per cent.

It will be using over 3,000 robots (roughly India’s annual purchase currently) to increase efficiencies.

Also in the works is a pan-India charging station infrastructure plan and even a cell plant, the main element that powers lithium ion batteries.

Yet, little is known about the scooter — its mileage, speed or price range — except that it will have two batteries that are easily removable.

And it will be priced close to an ICE scooter.

Rivals contend that Ola is introducing the app scooter built by Netherlands-based Etergo, which it acquired when it was o n the brink of bankruptcy.

And it has a long time to go before it develops its own R&D capability in manufacturing.

A senior Ola Electric executive said the product has been reworked substantially for India and only the design elements adopted from Etergo.

Still, Ola’s competition is formidable.

Bajaj Auto, which has launched an e-scooter under the Chetak brand (selling in limited quantities) is looking to set up a dedicated e-scooter plant of 0.5 million a year.

Hero MotoCorp has invested substantially in Bengaluru-based Ather Energy, which is building a factory in Tamil Nadu with an annual capacity of over 110,000.

Hero Electric, the largest player in e-two-wheelers, is investing Rs 600 crore to quadruple its capacity from 100,000 and has dropped prices to align with those of ICE scooters.

Hero Electric managing director Naveen Munjal is not about to lose his dominant share in e-scooters either.

“Today, we have 35 per cent share of the e-scooter market.

"As the market moves from low-speed to commuter scooters, we will surely continue to have 27-28 per cent in five years or, say, sell about 0.6 to one million,” he says.

Munjal also does not see any edge that a tech company has.

“This is hardcore manufacturing. You can buy software.

"It is about building dealer networks, after service, training people who can repair, that is the key.”

Ola insiders like to point out that even Tesla was not given a chance by analysts and car makers before it launched.

Whether Ola Electric can be India’s Tesla is a question that is wide open.