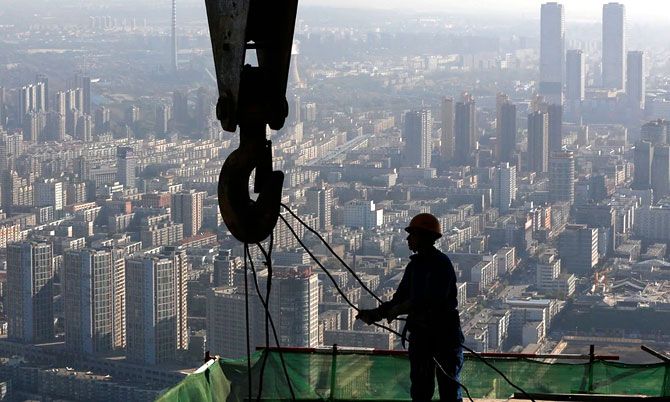

To redevelop cities as ‘smart’, investment of at least $10 billion is required. For 100 cities, it works out to $1 trillion

The National Democratic Alliance government’s ambitious Smart Cities programme will at best be able set up only 100 pilot projects in the first five years. Contrary to general perception, no ‘smart city’ will be created in the next five years, though a successful programme could see several smart colonies come up across the country.

A Business Standard analysis of the Smart Cities project shows its success will depend on three factors. First, the extent to which state governments and urban local bodies delegate their powers for the smooth functioning of special purpose vehicles (SPVs) mandated to run the scheme.

Second, how the private sector is accommodated in this SPV structure, while maintaining the delicate balance of power between the Centre, states and urban local bodies.

Third, how well the SPVs and the private companies involved are able to generate revenue from the real estate they develop in these ‘smart’ colonies. Considering government funds under the programme are no match for the investment required and the fact that there are few other sources to give the private sector good returns on investments, unlocking the developed land in these colonies will be critical.

Detailed queries sent to the Ministry of Urban Development remained unanswered till the time of going to print.

Smart colonies, not cities

To begin with, the government has announced it will soon select 20 cities from the shortlisted 98. Next year, it will select another 40, followed by 40 in the subsequent financial year. By end of this financial year, the first 20 cities are expected to put in place their SPVs to drive the projects.

The Union government has specified what a city needs to achieve to be labelled ‘smart’. It has set SPVs at least two targets in this regard. First, redevelop at least 50 acres or retrofit 500 acres or build a green-field project over 250 acres. For any of these, the SPV will have to provide an entire bouquet of smart services, such as electronic delivery of services, intelligent handling of municipal solid and waste water, smart parking and energy-efficient buildings.

Achieving this would take 3-10 years, depending on which of the three options a city chose, former urban development secretary Shankar Aggarwal had said in a presentation in Washington in January this year.

The second criterion requires any of the smart services from the entire bouquet being implemented across such a city, such as an intelligent traffic management system or smart metering.

The strategy document of the smart city programme reads: “Since the smart city is taking a compact-area approach, it is necessary that all residents feel there is something in it for them. Therefore, the additional requirement of some (at least one) citywide smart solution has been put in the scheme to make it inclusive.”

Jagan Shah, director of the National Institute of Urban Affairs, which is working with the ministry on the programme, says, “These are demonstration projects through which urban local bodies’ capacity to execute will be shown. This could later be replicated and scaled up to the city level.”

Consider, for instance, the case of Navi Mumbai, with a total area of 85,004 acres. To declare the programme here successful after five years, the authorities will have to either retrofit at least 500 acres with smart services, or redevelop 50 acres or build a new 250-acre smart colony. In addition, Navi Mumbai will have to provide only one pan-city service that could be labelled ‘smart’. Though a city could do more if it chooses to, the funds from the Centre are capped.

“Yes, one can say at the moment, we are looking at pilot projects in the selected cities. With the resources made available, it is a start,” says Arindam Guha, senior director of Delloite India, one of the consultants empanelled to help states develop smart-city plans.

For the programme, the Centre has committed Rs 48,000 crore (Rs 480 billion) through five years and states are expected to match this, ensuring a total corpus of Rs 96,000 crore (Rs 960 billion) for these pilots in 100 cities. The selection criteria favour cities already doing well, both in financial and management terms.

These 100 cities are also covered by the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation scheme, which will provide funds for basic utilities such as putting in place sanitation pipelines. Despite the convergence of other schemes to aid the development of smart cities, the funds will not suffice.

A US-India Business Council report on smart cities in India says to redevelop cities as ‘smart’, investment of at least $10 billion is required. For 100 cities, it works out to $1 trillion. The participation of private investors is essential and is encouraged at all stages by the government’s guidelines.

Developing smart pilot colonies, too, will require more money than currently being offered by the government. Take the case of the Smart City guidelines for the Bhendi Bazaar project in Mumbai. By official estimates, the redevelopment of only 16.5 acres is expected to cost about Rs 3,000 crore (Rs 30 billion). By contrast, under the Smart Cities programme, for a much larger pilots and pan-city activity, state and central support add up to Rs 1,000 crore (Rs 10 billion) through five years.

Who holds the reins?

The programme requires states to create an SPV. According to the guidelines, the SPV will have equal equity participation from the state and urban local body. It will be headed by a chief executive officer (CEO), who will have absolute executive powers to run the scheme. The Centre’s guidelines propose the CEO be appointed by the Centre; also, a CEO’s dismissal is only possible with the central government’s prior approval. Some experts say this condition might be modified.

The SPV will also have central government representatives on its board, along with those from the state and urban local bodies.

The Centre has recommended the CEO be delegated powers under the municipal and relevant state laws. It also suggests urban development boards, local self-governments and other state departments delegate relevant approval and decision-making powers to the SPV. This could lead to a turf war.

While the Centre recommends these powers be handed to the SPV, experts indicate it is unlikely that such powers will be transferred in entirety. State authorities, where favourable, might amend regulations for the pilot projects, while retaining the powers. Guha says clarity on these issues will emerge through the next phase of work.

Private sector participation in SPVs

The Centre encourages the SPVs to form further joint venture companies, create subsidiary companies and sign public-private partnership (PPP) agreements is required. Private participation in an SPV is allowed, as long as the state and the urban local body maintain majority and equal stake in the company.

However, the Union government guidelines in public domain are silent on whether the subsidiaries created by the SPV must necessarily be controlled by the state government and the urban local body. A senior official involved in the planning process says, “SPVs will be able to make further arrangements, as sanctioned by their executive boards. They can decide to hold a minority share in the subsidiary holding companies (with private investors as major shareholders).” Given the limited funds available with the authorities, such a mechanism could encourage private investors to step in to bridge the resource crunch.

“The SPV could spawn many such holding companies, each with private participation to deliver a component of smart city development, as it would be difficult to have all stakeholders for all components taking part in a single SPV,” says Guha.

The Centre has proposed to leave it to SPVs and state authorities to decide what model best fits their bill. Ajay Shankar, retired urban development secretary, says this will require innovation, adding matters of power delegation should be settled well before the private sector is brought on board.

Real estate: The money spinner

Private investors will essentially seek adequate returns on investment and identified streams of revenue. Mckinsey and Company, a consultant empanelled for developing city-specific plans, says in its presentation that there are four sources of funding available for financing smart cities — land monetisation, increased property tax and user charges, debt and PPP, and government support.

According to their estimates, 46 per cent of the overall capital required will have to be generated from selling land and real estate in the areas under development. While debt and PPP provide 20 per cent of the capital expenditure, government grants account for the remaining 34 per cent. Increase in property taxes and user charges will be used for operating expenses once the smart colony takes off, it suggests. The calculation was on a per capita basis, at 2008 prices.

“Urban local bodies have limited sources of funding; this challenge has to be addressed. Globally, revenue has been secured by capturing a higher value of land. Monetisation of land will play a key role. Instruments such as tax increment financing are also important,” says Shah.

The US-India Business Council has recommended real estate investment in the smart cities programme be classified as ‘infrastructure’. Its other suggestions on how to finance the programme, such as tax increment financing, are reflected in the government’s finalised scheme.

The need to monetise land arises because essentially, a smart city will provide several public services that might not generate adequate profits but are likely to have high costs involved. Also, it will encourage private sector participation. As the instances of East Kidwai Nagar and Bhendi Bazaar cited by the Centre show, scaling up the floor area ration (FAR) and changing the land-use pattern in an area is the key to monetising the land.

A higher FAR leads to more built-up area per unit of land. The additional built-up area is then sold by the developer to earn returns. Parallels can be found in the development of Gurgaon in Haryana and Greater Noida in Uttar Pradesh.

M Ramachandran, retired urban development secretary, however, says projects based on land monetisation could face challenges, given the slump in the property market. He believes user charges and other sources of revenue to be generated by the urban body will have to be considered as keenly. Mckinsey’s report notes these could be utilised in meeting operating costs.

While the Centre works out these modalities and fine-tunes the regulations the Union urban development minister has announced, the list of the first 20 cities will be out soon. The smart-city project enters round two.