India could allow commercial coal mining by foreign companies if they set up units in the country, opening the door for global giants like Rio Tinto to access the world's fifth-largest coal reserves, a source familiar with the matter said.

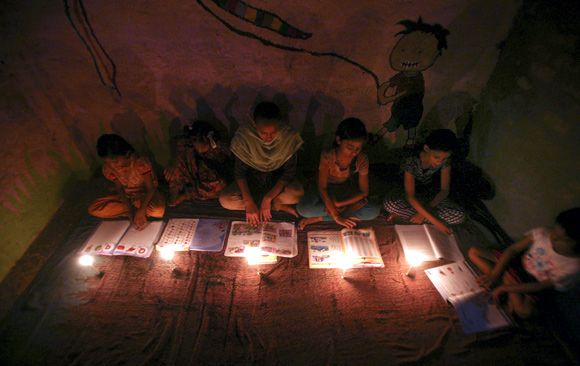

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's decision to open commercial coal mining to private players is a key step towards bringing order to the country's chaotic power industry and ending the chronic blackouts that impede its economic rise.

Photograph: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

Nearly a quarter of a century after India embraced economic liberalisation, many businesses still rely on costly back-up generators for round-the-clock power and a third of its 1.2 billion people are still not connected to the grid.

As of now, only Indian power, steel and cement companies can mine coal for their own consumption. Commercial mining is dominated by state-owned Coal India Ltd.

But the government now plans to allow companies like Rio Tinto India to mine coal commercially after it completes the auction of 74 coalfields for the exclusive consumption of Indian companies' power, cement and steel plants, said the source, who did not want to be identified as he is not authorised to speak to the media.

In a 27-page executive order posted on the Coal Ministry's website on Wednesday, the government said any firm incorporated in India may be allowed to mine coal for their own consumption or sale, ending a 42-year-old ban.

The document did not make any direct reference to allowing foreign firms.

Rio Tinto India Managing Director Nik Senapati declined to comment.

Other foreign players that may show interest in India are BHP Billiton and US firm Peabody.

A Coal India official said it would be natural for the government to allow deep-pocketed foreign companies to mine coal, given the need to invest heavily and quickly raise output.

MODI'S REFORMS

Opening up the industry would ultimately boost production of a raw material that generates three-fifths of India's power supply, and it will pile pressure on Coal India to produce more.

"This is a first step but a very important one," said Manish Aggarwal, head of KPMG's energy and natural resources practice in India.

"What the government is really saying is that we will focus on domestic coal and on renewables to meet our energy needs. . . India needs the latest technology, the latest equipment and international expertise if it is to raise coal production."

As chief minister of Gujarat state before becoming prime minister, Modi prided himself on supplying uninterrupted electricity, and repeating that feat at a national level is one of his priorities.

It will not be an easy task.

India sits on the world's fifth-largest reserves, and yet Coal India, which has enjoyed a monopoly on commercial mining, has consistently failed to meet the rising demand of an economy that has grown rapidly since the reforms of the 1990s.

Instead, wretched inefficiency has turned India into the world's third-largest importer of coal.

Last month, the Supreme Court cancelled more than 200 coal block licences it ruled were allocated illegally in a case that has become emblematic of the dysfunctional nature of the industry.

The government will re-auction the coalfields to private firms within four months. For the first time, revenue from the concessions will be paid to the states where the blocks are located, creating an incentive to speed up project approvals.

"Modi wants to include incentives . . . by giving the opportunity to coal-rich states to earn royalties," said a retired bureaucrat who helped Modi tackle power shortages in Gujarat.

NEXT STEPS

Boosting the supply of energy is only half the problem, industry experts say, and Modi is expected to now push individual states to reform the rickety distribution model.

Boosting the supply of energy is only half the problem, industry experts say, and Modi is expected to now push individual states to reform the rickety distribution model.

India's installed energy generation -- more than half of it powered by coal -- has risen 20 per cent in the last three years, and the peak power deficit fell to 5.1 per cent in June from 9 per cent in 2012, according to government data.

But cash-strapped distributors, their tariffs capped and facing rampant power theft, have invested little in new transmission lines.

This has meant that, for all the extra power generated, not enough is delivered to consumers.

"This is not a complete solution... Fixing the transmission and distribution side is equally critical," said Aggarwal.

(Additional reporting by Tommy Wilkes; Editing by Douglas Busvine and Ryan Woo)