Qimat Rai Gupta even sold oil on a cycle in the villages of Punjab, says Bhupesh Bhandari recounting his amazing story.

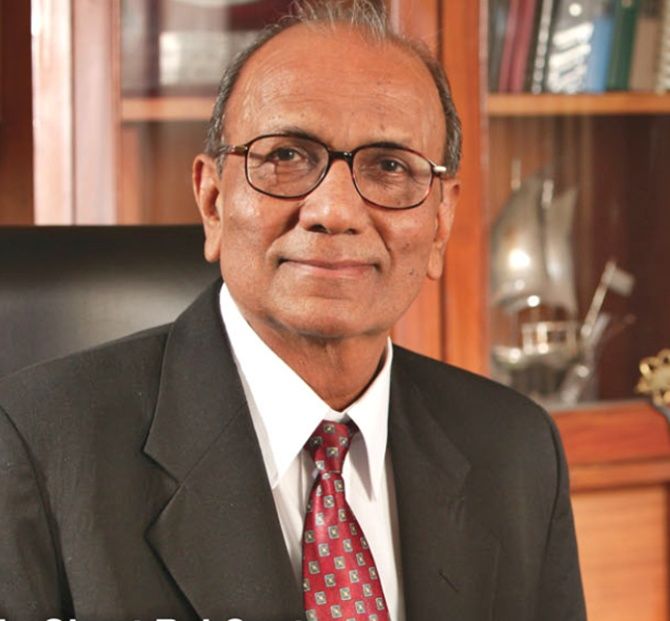

Two weeks ago, Qimat Rai Gupta of Havells India passed away quietly. Born in a low-income family of Malerkotla in Punjab, he was worth almost $2 billion when he died at the age of 77 after a cardiac arrest.

Yet the businessman kept a low profile and stayed focused on his work. He created minimum fuss in life - and in death.

He always looked contended and unhurried; at times, he came across as rather taciturn. Yet he ran Havells with authority.

There was never any doubt that he called the shots in the company. He would take stock of the situation every morning in a meeting with his key executives, including his son (Anil) and nephew (Ameet).

Nobody dared to skip these meetings. His house in Civil Lines was big but not ostentatious. He travelled in simple cars, though he could easily afford the most expensive set of wheels in the world.

That's because people from humble origins know fortune is fickle. And Gupta's roots were truly modest. Early in life, he had even sold oil on a cycle in the villages of Punjab.

In 1958, he moved to Delhi and, along with a relative, started a shop for electrical equipment at Bhagirath Place, a crowded market in Old Delhi. Over the next decade or so, he painstakingly built the business.

His big opportunity came in 1971 when he acquired a company called Havells. Contrary to the perception that the name is of German extraction, Havells is the anglicised name Haveli Ram Gandhi, grandfather of fashion designer Rohit Gandhi, gave to his switchgear company when he started it several decades ago.

His big opportunity came in 1971 when he acquired a company called Havells. Contrary to the perception that the name is of German extraction, Havells is the anglicised name Haveli Ram Gandhi, grandfather of fashion designer Rohit Gandhi, gave to his switchgear company when he started it several decades ago.

He subsequently sold the company to Gupta, who was one of his distributors. There was no looking back for Gupta after that. From switchgear, he diversified into newer areas like cables, lightings, appliances, fans and geysers.

When I first met Gupta, he used to operate out of a cramped office in Civil Lines. The interiors may have been chaotic, but the energy was palpable.

Cubicle walls had gaps so that senior executives could talk and exchange papers quickly. Some years ago, the company moved lock, stock and barrel to a swank 130,000-square-ft office called QRG Towers spread over 3.5 acres in Noida.

Cubicle walls had gaps so that senior executives could talk and exchange papers quickly. Some years ago, the company moved lock, stock and barrel to a swank 130,000-square-ft office called QRG Towers spread over 3.5 acres in Noida.

This was also the time Gupta decided to reinvent the company. He realised that Havells was competing with strong brands in the market: Philips and Osram in lighting; Crompton Greaves, Orient, Polar and Khaitan in fans; and Finolex in cables.

Still, most of the rivals did not spend more than one or two per cent of their turnover on brand promotion. Moreover, a large part of their promotion was below the line. In 2007, Gupta decided that if Havells had to break the clutter, it would have to radically outspend rivals.

Still, most of the rivals did not spend more than one or two per cent of their turnover on brand promotion. Moreover, a large part of their promotion was below the line. In 2007, Gupta decided that if Havells had to break the clutter, it would have to radically outspend rivals.

From around Rs 15 crore (Rs 150 million), the budget for brand building was bumped up to Rs 60 crore (Rs 600 million): over four per cent of the company's then turnover. It signed on Lintas Lowe to devise a campaign, and R Balki, the agency's chairman and chief executive, personally supervised it.

The brand, it was decided, would talk to men between 25 and 45 years of age (electrical fittings are selected by men, tiles and bathroom fittings by women), and for that, cricket would be the right medium.

Fortunately for Havells, that was the time India had done badly in the World Cup in the West Indies. Cricket properties were going dirt cheap, and Havells was able to strike some amazing advertising deals.

Ever since, Gupta kept the bar for advertisements high. Some didn't work, like the one for Havells fans that showed people wading through a pool of sweat, but mostly they were of a high quality.

Ever since, Gupta kept the bar for advertisements high. Some didn't work, like the one for Havells fans that showed people wading through a pool of sweat, but mostly they were of a high quality.

One immediate benefit was that the discount at which Havells sold its lamps and fixtures to market leader Philips soon vanished.

Gupta's biggest challenge came soon thereafter. In 2007, Havells acquired Sylvania for euro 227 million. Not only was it his first overseas foray, but Sylvania was much bigger than Havells.

Digesting the acquisition was never going to be easy. The slowdown of 2008 drove Sylvania into the red. As a result, the share price of Havells crashed to a third. There was pressure from the banks to infuse capital into Sylvania to resurrect it, which would have bled Havells further.

Some advised Gupta to sell off the company and cut his losses. Still others told him the new office in Noida was unlucky and he should get rid of it as quickly as possible. Instead, he decided to take the challenge head on.

One day in December 2008, Gupta summoned Anil and Ameet to his office and read out the riot act to them. Sylvania's plummeting performance, he told the two, was a blow to Havells' reputation.

If they cannot turn it around, they would never again be able to do any acquisition. No banker would ever support them again. It was a challenge, but also an opportunity to prove their mettle.

They had, Gupta told them in no uncertain terms, not run Sylvania well and had been happy to play the role of a financial investor.

Over the next few months, the duo consolidated in South America, downsized in Europe, relocated the nerve centre from New York to Noida, and migrated production to low-cost factories in China and India. By 2010, Sylvania had turned the corner.

Gupta had an extraordinary life, and he chose to live it away from the limelight.