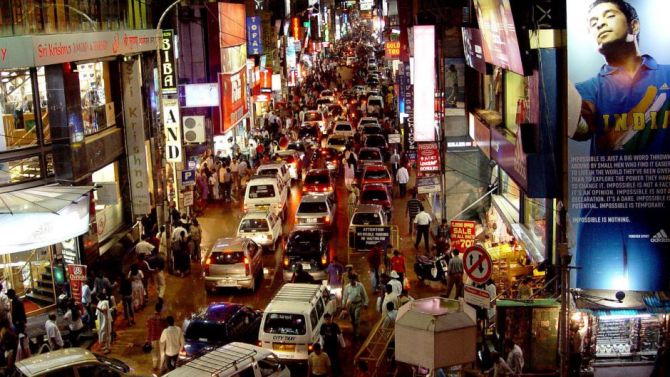

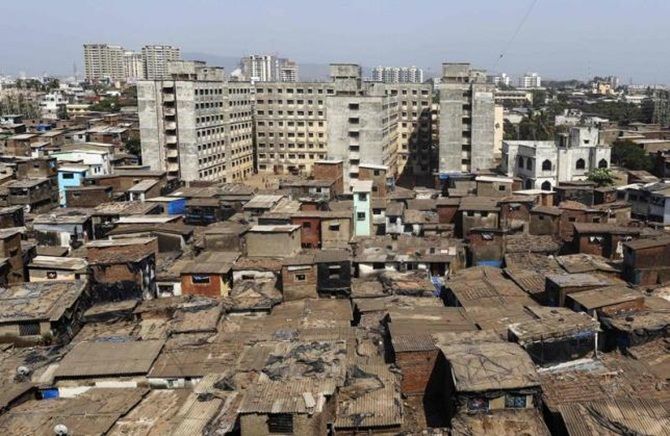

India’s cities are bursting at the seams because poor people are migrating to them in search of work and finding a place to live only in slums, old and new, says Subir Roy.

Photograph: Reuters

What is the progress made by the Smart Cities project at the end of the first year of its five-year life?

Are the right priorities driving the 100-odd cities chosen by the Centre for the purpose?

Business Standard recently ran reports featuring four smart cities and, for comparison, Lavasa, a smart city conceived a decade ago under private initiative.

Bhubaneswar, Surat, Visakhapatnam and Pune – all among the top 20 smart cities – are in a way not representative of the whole.

They were already a bit smart, had a positive urban persona, to begin with.

So how have at least the best among the smart cities got off the ground?

They have just about got going. All have formed the special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to oversee the project in order to free it of the many constraints that inhibit a government department.

All are in some stage of appointing consultants and getting them to secure and approve plans for the individual components of the project.

They have two positives: funding is in sight, a bit of it already there, and at least two, Bhubaneswar and Visakhapatnam, will get foreign assistance.

Being a high profile project, the various SPV boards have capable members and will likely have in time competent officials to run the show.

Thus these cities do not have several critical shortcomings that plague most Indian cities like shortage of managerial skills and resources and uncaring state governments.

The smart cities have set out to be showpieces by relying strongly on information technology solutions which will hopefully bring about improvement in areas like transport, electricity and water supply management.

A digitised control center to monitor and respond promptly to developments will also be a great help. There is nothing wrong with these initiatives but the top priority should be something else.

India’s cities are bursting at the seams because poor people are migrating to them in search of work and finding a place to live only in slums, old and new.

The ratio of people living in “informal” housing or under slum-like conditions is steadily rising.

It depends on how you draw the lines to define city limits but realistically half of Mumbai lives in slums.

The growth of slums is the dominant feature of the urbanisation that we constantly refer to as the engine of growth which will take the entire economy forward.

But cities can function as engines of growth only if they are not health hazards and cauldrons of social unrest posing severe law and order challenges.

So the primary task is to retro fit slums so that they cease to be so.

Instead, the specific areas chosen for development are in some cases already quite developed, as in the case of Pune.

Bhubaneswar has more sensibly chosen the central area near its railway station for concerted development.

The second priority needs to be a total garbage solution involving segregation, recycling and composting.

This will drastically reduce the need for landfill space and thus address the crisis being created by dwindling landfills in cities across the country.

Bengaluru, in many ways the symbol and hope of knowledge-driven modern India (logically it should be the smartest city in the country), with also a strong civil society presence (organisations like Hasiru Usiru are trying to get citizens to take initiatives across urban issues), is literally stinking because of its inability to clear all the solid waste in time.

To solve Bengaluru’s garbage problem, you don’t need highfalutin IT solutions (the leitmotif of the smart cities project) proposed by vendors, but the ability to counter entrenched interests and put in place common sense solutions that can be worked by a minimum level of governance.

It is not as if Indian cities can’t do it. Pune has tackled solid in an exemplary manner.

The third priority needs to be safe drinking water for all along with water harvesting and treatment plants. Those who can pay should pay for their water.

A major offender is Kolkata where the political dispensation refuses to charge the well-off even in gated communities for the water they consume.

The slum dweller is already paying with the time she has to devote to fetch the water.

The fourth priority needs to be an affordable (not costly tokenisms like metro rail) and reliable non-polluting public transport system (electric or CNG buses) that does not choke the city with its exhaust fumes.

Not only is air quality in Indian cities among the worst in the world, the economy pays heavily through energy wasted (idling cars and buses) and time lost in traffic jams.

The health and efficiency gains reaped by cities which take care of their solid waste the right way, deliver safe drinking water to all and have efficient non-polluting public transport systems that make car trips mostly unnecessary, will make them proper engines of growth.

If you add to it the socially uplifting impact on a slum dweller (and the resultant rise in his economic efficiency) who gets to live in non-slum like conditions, you know where to begin to make cities smart.

It is not that these issues are not addressed under the smart cities rubric (Surat talks of building just 4,350 affordable dwelling units!) but the sense that they come before all else is missing.

The lesson from Lavasa is that even after 10 years, a text book smart city can remain in limbo — be just a weekend resort.