Panagariya has advocated a more liberalised spending, arguing that greater capital expenditure could relax some of the infrastructure bottlenecks facing the country, says Ishan Bakshi.

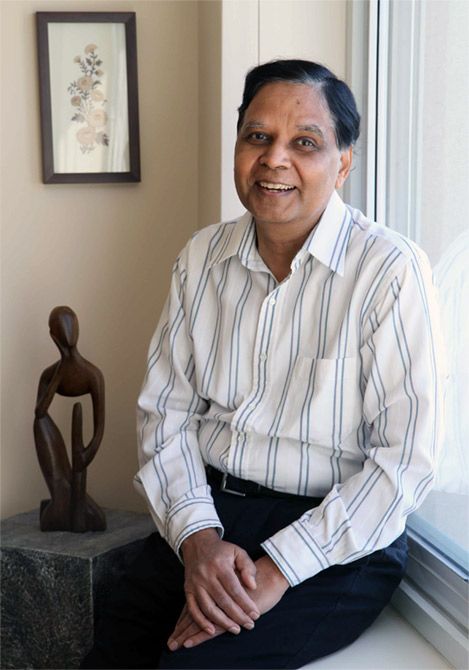

Arvind Panagariya, to many, is the obvious choice for the post of vice-chairman of the newly constituted NITI Aayog.

Not only is he an experienced economist with a stellar academic record, but he is also one of the few economists to have volubly criticised the economic policies of the previous government while lending his intellectual support to Narendra Modi in the run-up to the general elections last year.

But there is more to him than just his leanings.

Mentored by Jagdish Bhagwati, and currently the Jagdish Bhagwati Professor of Indian Political Economy at Columbia University, 62-year-old Panagariya has served as chief economist at the Asian Development Bank, and worked at the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization.

In the days leading up to Modi's election as the prime minister, Panagariya, with co-author Bhagwati, had showered praise on the 'Gujarat model', showcasing it as development driven by growth and private entrepreneurship.

Holding the model superior to the so-called Kerala model, popularised by their ideological rival Amartya Sen, the duo strongly advocated against the redistributionist model pursued by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government.

Yet to describe him as ideologically motivated would be unfair, say those who know him.

His friends call him a pragmatist who is guided by evidence rather than ideology. Much shouldn't be read, therefore, in his views on issues such as centre-state relations, education and health contrasting sharply with those advocated by the previous regime.

Panagariya, who was critical of UPA's Food Security Act and National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, has repeatedly made the case for transitioning towards cash transfers of government benefits.

He has argued that replacing the current subsidy regime, which suffers from a high level of leakages, with an efficient system of cash transfers would ensure benefits reached the targeted poor.

His strong views on the subject suggest that putting in place such a subsidy regime is likely to be a top priority for him at the NITI Aayog.

Panagariya has also repeatedly called for market reforms - in land and labour, in particular.

He contends that in contrast to the development trajectory of most Asian countries, India has effectively bypassed the manufacturing stage, transitioning from an agricultural to a service-oriented economy.

But as the service sector has a limited capacity to absorb labour, the surplus labour force currently engaged in agriculture has nowhere to go.

The imbalance in the economy - 50 per cent of labour is in agriculture while the sector accounts for less than 15 per cent of GDP - can be rectified only if labour-intensive manufacturing is developed in India.

However, he sees the country's stringent land and labour laws as impediments in this objective. Rajasthan, where Panagariya was a member of the state economic advisory council, was the first to propose changes to land and labour laws.

The economist's views on government spending, however, go against those advocating fiscal prudence in the current scenario.

Panagariya has advocated a more liberalised spending, arguing that greater capital expenditure could relax some of the infrastructure bottlenecks facing the country.

With the chief economic advisor, Arvind Subramanian, also making a similar point in the mid-year review, it is likely that the government will have a rethink on this issue.

Those who think that Panagariya's appointment heralds a new age of right-wing economics in India might want to consider what he told Reuters last year.

Stating that he did not support a Thatcherite agenda (British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, along with US President Ronald Reagan, was a key advocate of centre-right economics), he said that though "India should give markets a freer rein, it still needed growth in social spending as the country was home to a third of the world's extremely poor."

The policy movement, therefore, may not be from the left to the right, but from far left of centre towards a centrist position.

.jpg)