‘That an Indian can lead the world’s top software company is an important milestone for Indian Americans and for America. But the larger message is for India itself: Imagine what Indians can achieve at home if they put their differences aside and start helping one another,' says Vivek Wadhwa.

‘That an Indian can lead the world’s top software company is an important milestone for Indian Americans and for America. But the larger message is for India itself: Imagine what Indians can achieve at home if they put their differences aside and start helping one another,' says Vivek Wadhwa.

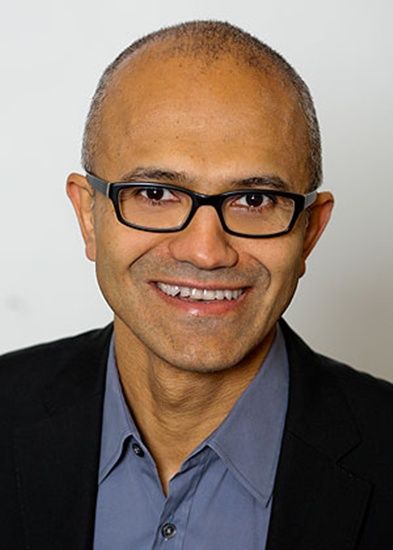

Satya Nadella is highly qualified and will do a lot of good for Microsoft.

I wish him lots of success because Microsoft has many challenges ahead. Its core market -- the PC -- is shrinking. Tablets and smart phones, which predominantly run on Android and iOS, are eclipsing it.

His job won’t be easy. But Nadella has done wonders in building the cloud business, so if anyone can beat the odds, it is him.

Nadella was clearly the best choice for this job because he understands the cloud and mobile and built a very successful business for Microsoft.

I don’t know Nadella personally, but know some people who know him very well. They are in awe of him.

What surprises me is that a company that had no senior Indian executives until the 1990s is now appointing an Indian as CEO. This shows how far the industry and America have come.

When Vijay Vashee joined Microsoft in 1982, he was just one of two Indians at the 160-person company. It added several more recruits from India, mostly IITians, over the years. They held low-level technical positions.

Vashee became the first Indian to break through Microsoft’s glass ceiling in 1988 when he was named general manager for Microsoft Project.

In 1992 he was asked to head the fledgeling PowerPoint Division and helped grow this from a $100 million to a billion dollar business.

About the same time as Vashee, Indians in Silicon Valley began breaking glass ceilings. They all faced the same hurdles: A belief that Indians made great engineers, but were not capable of becoming managers -- certainly not CEOs.

A common perception was that they didn’t know how to delegate authority and could not lead companies. Satya Nadella or Sundar Pichai would not have made the list a few years ago because of the negative stereotypes.

This shows how much the technology industry -- and America -- has changed.

How did this transformation happen?

Very simply: Indian Americans started helping Indian Americans -- regardless of their caste, religion, and regional heritage.

They formed networking organizations such as TiE (The IndUS Entrepreneurs) to teach others about starting businesses, and to bring people together.

The first generation of successful entrepreneurs -- people like Vijay Vashee -- served as visible, vocal, role models and mentors to the next. And they provided seed funding to members of their community.

This helped Indians achieve extraordinary success. Research by my team at Duke, UC-Berkeley, and Stanford showed that as of 2005, 52.4 percent of Silicon Valley’s companies had a chief executive or lead technologist who was foreign-born and Indians founded 25.8 percent of these companies. This proportion increased to 33.2 percent in 2012.

Indians, who constitute only six percent of Silicon Valley’s working population, start roughly 15 percent of its companies. That is quite a feat to achieve in the most competitive, entrepreneurial, and innovative place on this planet.

That an Indian can lead the world’s top software company is an important milestone for Indian Americans and for America. But the larger message is for India itself: Imagine what Indians can achieve at home if they put their differences aside and start helping one another.

(Also), if he couldn’t get an H1B visa or a Green Card, he would have had to leave the country. This would have been a big loss to Microsoft.

The sad thing for America is that tens of thousands like him are being chased away every year because of America’s flawed immigration policies. There are probably several Microsoft-type companies that weren’t started in the US because of our flawed immigration policies. This is sheer stupidity.

As told to George Joseph and Suman Guha Mozumder

Vivek Wadhwa, is a Silicon Valley entrepreneur; vice president, Research and Innovation, Singularity University; fellow at Stanford Law School; and a director of research at Duke University.