'Some experts believe that in the next few years, the difference between gross market borrowings and interest paid by the government will disappear.

'When this happens, some believe that it would be a debt trap for the Central government, since it would be borrowing from the market to service past debts.'

Indivjal Dhasmana reports.

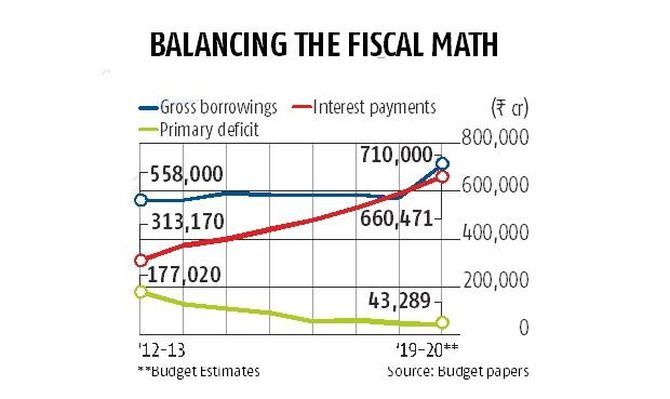

The gap between gross borrowings of the government and the interest payments by it for past debts has been coming down progressively over the years, with some exception though.

This means that market borrowings are increasingly being used to pay interest on past loan rather than the current expenditure.

The gap in 2012-13 stood at a whopping Rs 2.4 trillion which is projected to come down to Rs 49,529 crore in 2019-20.

In between, there was one notable exception in 2018-19 when gross market borrowings were less than interest payments.

The interest payments was higher by Rs 16,570 crore that year.

This happened because the government resorted to borrowings other than market loans, such as advances from National Small Savings Fund (NSSF).

Broadly, the difference between gross market borrowings and interest payments is primary deficit.

This deficit is equal to fiscal deficit sans interest payments or the deficit that is used because of the current expenditure.

However, since the government resorts to NSSF borrowings these days, it does not exactly become primary deficit.

As cited above, the gap is projected to be Rs 49,529 crore in 2019-20.

However, primary deficit is estimated at Rs 43,289 crore for the year.

The difference between primary deficit and gap between gross market borrowings and interest payments -- Rs 6,240 crore -- is the loan the government is projected to take from other sources, particularly the NSSF.

Some experts believe that in the next few years, the difference between gross market borrowings and interest paid by the government will disappear.

When this happens, primary deficit would be equal to the borrowings from other sources.

In fact, the government aims to eliminate primary deficit by 2020-21, according to the Medium Term Fiscal Policy-Cum-Fiscal Policy Strategy Statement, presented with the Budget papers.

When this happens, some believe that it would be a debt trap for the Central government, since it would be borrowing from the market to service past debts.

But some experts believe that it would be beneficial for the economy since the government is not borrowing to finance its current expenditure.

Devendra Pant, chief economist at India Ratings, said a lower primary deficit will help in debt sustainability, keeping other things constant.

DK Srivastav, chief policy advisor at EY, said larger the primary deficit in overall fiscal deficit, the larger is the need for borrowings to fund the current expenses.

Primary surplus, he said is needed for servicing past debt.

It is a transition point to say that past debt is large, but it does not mean that it has become unsustainable.

He said the primary deficit should be targeted from the debt sustainability point of view.

Primary surplus would mean that debt to gross domestic product or GDP would fall.

Aditi Nayar, principal economist at ICRA, said the proportion of government securities as a source of funding the Centre's fiscal deficit has eased of late, especially on account of greater reliance on NSSF.

Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at CARE Ratings, does not want to look at Budget numbers in such an isolated fashion.

He said money is fungible, so the numbers should be looked at holistically.

"You can always say that government borrowings are used to fund subsidies, why only interest on past debts.

"I would not go with the arguments to look at these numbers in an isolated way, though these opinions may be valid in their own ways," he said.

The primary deficit is a key aspect of fiscal consolidation for debt sustainability.

In his dissent note on the NK Singh committee report on the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM), former chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian had advocated relying on primary deficit for the purpose of debt sustainability.

"I would propose a simpler architecture, comprising just one objective: placing debt firmly on a declining trajectory.

"To achieve this, the operation rule would aim at a steady but gradual improvement in the general government primary balance until the deficit is entirely eliminated," he had said.

The FRBM panel had relied on the targets for fiscal deficit and revenue deficit, with a provision of an escape route of 0.5 percentage points in a year, in a situation of an upturn or downturn.

It had said the Centre should ensure that debt of the government (Centre and the states) does not exceed 60 per cent of GDP by 2022-23, with the Union government debt at 40 per cent of GDP by that year.

In fact, towards the fag end of the previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, the then Planning Commission deputy chairman Montek Singh Ahluwalia had advocated relying on primary deficit.

He had said primary deficit is the internationally accepted measure of fiscal consolidation because interest rates can vary for reasons other than government belt tightening.

In their book, Federalism and Fiscal Transfers in India, C Rangarajan, former chairman of the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council, and D K Srivastava, then director of the Madras School of Economics, have recommended that primary deficit be brought back into focus if debt has to be contained in proportion to GDP.

Primary surplus must be sustained for the debt-GDP ratio to fall, argued the authors.