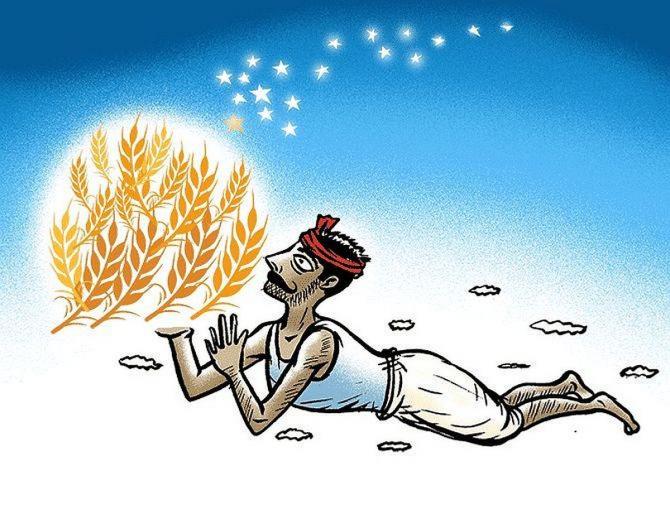

Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Rajasthan go to the polls in less than a year. They produce important agri-commodities. The Centre is in a dilemma: Higher prices will be inflationary, lower prices will trigger farmer wrath. The time to decide on strategy is now.

Sanjeeb Mukherjee reports.

In the coming few weeks, agriculture markets in North and Central India will be full of wheat, mustard, and chana — the three main rabi crops grown in these parts.

Not only will the price trajectory of these determine the course of food inflation in the months to come, but it could also have a wider impact on the rural economy in the main growing states for these crops.

Wheat and chana are largely grown in Madhya Pradesh (MP).

Rajasthan is a major producer of mustard and wheat as well.

In Chhattisgarh, too, chana is among the most important pulses grown during the rabi season.

The three states are also among the big ones that will go to polls ahead of the 2014 general elections and where the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is either in power or is the main challenger.

The BJP lost power in all three states in the elections held in 2018.

At the time, Shekhar Dixit, president of the Rashtriya Kisan Manch, a farmer’s body, had blamed the state government’s agricultural policy for the losses.

“The dual nature of the BJP leaders, while dealing with the grievances and woes of farmers, led to its poor performance in MP, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh…

"Farmers in both states were angry over the agricultural policy decisions adopted by the BJP governments.

"There has been agricultural distress in both the BJP-ruled states in the past five years,” he said after the 2018 results showed a slide in BJP vote.

In MP, learning from the reverses, the BJP, in government now because of defections from the Congress, has taken several steps to assuage the feelings of farmers that included topping up the Centre’s PM Kisan scheme with its instalment of Rs 4,000 per annum, increased procurement of wheat and other crops from farmers, among others.

In Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, too, the ruling Congress government has taken many steps to ensure farmers are kept happy.

These include debt relief and increased procurement of paddy in the case of Chhattisgarh, among several others.

Although elections to state assemblies are nearly a year away, both the state and central governments are trying to ensure farmers have nothing to bicker about.

But both face a dilemma.

If governments move too aggressively to control food inflation by forcing down prices, they run the risk of angering farmers in poll-bound states; but if inflation lingers, it could hit consumers.

Already, high wheat and atta prices this year have thrown domestic budgets off-kilter — which is why the Centre first banned wheat exports and since February, has started aggressive open market sales to liquidate wheat from its inventory.

The January decision to end the extra free foodgrain distributed under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana is also being interpreted in some quarters as a step to save enough quantities of wheat for effective intervention in the case of price rise, apart from curtailing rising food subsidy that was becoming unsustainable.

Meanwhile, market players are confident that wheat prices will trade above the minimum support price (MSP) in most markets this year but that would mean that fewer farmers might sell wheat to the central pool when the procurement season starts in the next few weeks, thereby making it harder for it to replenish stocks.

A bonus above MSP could be employed to encourage farmers but that would widen the cost of procurement.

However, a bumper production could change much of these probabilities, provided the Centre has avenues to keep prices supported.

In the case of mustard, traders expect prices to hover around the MSP of Rs 5,450 per quintal.

“Mustard seed prices have lost 5.6 per cent this month (February) so far, after losing 6.75 per cent in January 2023 and currently trading at a 22-month low of Rs 5,900 per quintal.

"A higher carry-over stock, coupled with record production, will drag prices down further towards Rs 5,500 per quintal,” Tarun Satsangi, assistant general manager (commodity research) at Origo Commodities, had told Business Standard few weeks back.

In the case of chana, the market feels that if prices remain below the MSP of Rs 5,335 per quintal when the new crop arrives, the government might have to aggressively intervene to prop up sentiment.

Good stocks with farmers and traders are also expected to keep chana prices capped, observe traders.

The Centre in its Second Advance Estimates released earlier this week, pegged the production of chana at 13.63 million tonnes (mt) this year — 0.66 per cent more than the same period last year.

It projected the production of mustard, which is the main oilseed grown during the rabi season, at a record 12.81 mt — 7.11 per cent more than last year.

Both the Centre and state governments know that delays in decisions related to the pricing of agri-commodities can lead to adverse political outcomes.

And they are determined to avoid making that mistake.