Budget should raise revenues & reduce spending to increase capital expenditure, without compromising fiscal deficit target excessively, says Jaimini Bhagwati.

It is that time of the year. Newspapers and television channels are in a competitive frenzy making pronouncements on the Union government's Budget, to be presented to Parliament on February 29.

It is that time of the year. Newspapers and television channels are in a competitive frenzy making pronouncements on the Union government's Budget, to be presented to Parliament on February 29.

The frantic voices cannot be muted and one remedy is to join the circus.

This article preaches the basics which tend to get obscured, as Macbeth puts it, in all that "sound and fury".

Although India's GDP grew by 7.3 per cent in the last quarter of the calendar year 2015, the index of industrial production (IIP) fell by 1.3 per cent in December 2015.

Again, while the trade deficit has shrunk, exports were down for the 14th straight month in January 2016. And, Indian equity indices are lower by about 20 per cent in the past one year.

In this environment of uncertainty for long-term investors, the strait-jacketed thinking is that the finance ministry should adhere strictly to its fiscal deficit objective of 3.5 per cent of the GDP for 2016-17.

Going by newspaper reports JP Morgan appears to be running monetary policy, suggesting that if the government sticks to its fiscal target, a repo rate cut of at least 25 or even 50 points would follow.

The European and Japanese experience has amply demonstrated that even with negative nominal interest rates there is little appetite for lending if banks are laden with impaired debt.

Indian public sector banks, which provide the bulk of long maturity loans, are groaning under the weight of stressed assets.

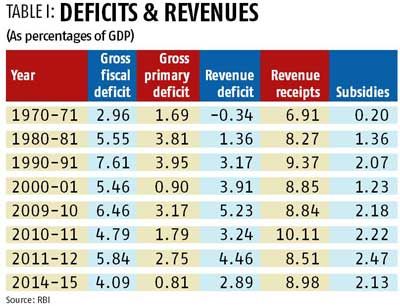

Table I provides a sense of what lies at the core of the Union government's fiscal choices.

It is apparent, even without the benefit of hindsight, that gross primary deficit (revenue deficit less interest payments) should not have been allowed to rise above three per cent of GDP in 2009-10.

It could be argued that the government had no option but to raise expenditure after the sharp slowdown of the global economy post 2008. However, why has government not done more to raise revenues, which in 2014-15 were at about the same level as 34 years ago in 1980-81?

As the Indian government's Budgets are not accrual-based, contingent liabilities are not recognised.

To that extent, the deficit numbers are understated and probably not comparable across time.

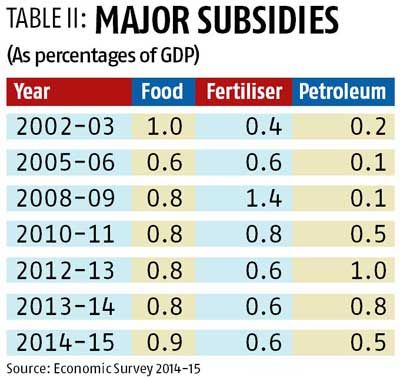

Table II lists amounts spent on three major subsidies in the past 15 years.

It is incumbent on the government to provide food subsidies, which would be more efficiently achieved through cash-based transfers to bank accounts.

The same line of reasoning holds for the petroleum subsidy.

However, eliminating plant-specific fertiliser subsidies and reducing the enormous waste and worse in Railways, Air India and at the Food Corporation of India have to be priorities to provide more fiscal elbow room.

Looking back, it was not just the balance of payments crisis which triggered the sweeping economic reforms post 1991.

The dissolution of the Soviet empire was one of several other factors which convinced fence-sitters within the government's decision making circles.

Ex-post we know which business empires withered because they would not change. The sense now is that there is an unspoken consensus for weak reforms.

This is probably because a different set of major corporations and many among the political executive prefer incrementalism rather than the uncertainty which would be unleashed with wider and deeper reforms.

Fiscal hardliners maintain that the government cannot plan let alone execute long-gestation projects efficiently and would not be able to resist pressures to increase consumption expenditure.

The backlog of the slowdown caused by Supreme Court judgements plus land acquisition hurdles means that private investments are not forthcoming for long-gestation projects.

Further, the current labour laws and a slew of well-intentioned but difficult-to-correctly-implement legislation, for example on payment of wages/bonus/gratuity/fringe benefits, rent control, stamp duties, service taxes, copyright often add up to become show-stoppers.

However, the BJP is in power with overwhelming majorities in several large states.

The central government could support completion of stalled infrastructure projects and starting of new ones in these states.

This should have a strong demonstration effect in non-BJP administered states.

Infrastructure development in G-7 countries and China was mostly funded by government and public sector bodies. It follows that the employment-boosting option is for government to step "once more unto the breach".

A significant proportion of the banking sector's difficulties have been caused by private entities claiming force-majeure for their inability to repay.

Hence, for prudent future long-term loans instead of public sector banks, India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL) could be the preferred lead-lending institution.

The government needs to appoint professionals with private sector project experience in IIFCL and consult private banks particularly those with experience of longer term lending in China.

The present value of the central government guarantee for IIFCL bonds should be accounted for as capital expenditure.

To sum up, the Budget should seek to raise revenues and reduce wasteful public spending in order to increase capital expenditure without compromising the fiscal deficit target of 3.5 per cent excessively.

The central government has to govern and the annual Budget is too important an opportunity to miss.

As we have witnessed repeatedly in the last few decades, lack of governance leads to the Supreme Court, the central bank and others coming up with short-term solutions with negative longer-term consequences.

The writer is a professor at Icrier. Views expressed are personal.