'There are deeper, underlying, forces at work and we need institutional arrangements to guard against them.'

A year after he left the Reserve Bank of India, months before his three-year tenure finished, Viral Acharya, former deputy governor, in his latest book has described how fiscal dominance is the biggest bane of the banking system in India.

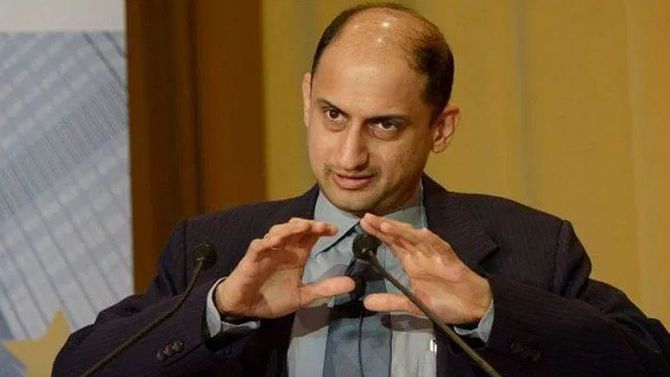

"Pressure is pervasive. It is not that just one aspect of central banking policy is under pressure," Dr Acharya tells Tamal Bandyopadhyay in the first of a two-part interview:

You have said the RBI had lost its governor (Urjit Patel) on the altar of financial stability. What about you? You too left six months ahead of the end of your term. Along with Patel, you had put a big fight with the government for the RBI's autonomy. Aren't you too a victim?

You have delivered the first ball of the Test match with a bouncer.

Let me duck it even though I am wearing a helmet.

What I wanted to stress throughout the book and the message I am trying to send is that it is not so much about personalities. There are deeper, underlying, forces at work and we need institutional arrangements to guard against them.

I do think the central bank was under pressure, especially when the horizons of the government got short.

Resistance was put up when some of us were keen to avoid the excesses and we were trying to prevent those from occurring again... It came at a cost to many of us.

We ought to focus on why, even after acknowledging that the problem is there, having put in place the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, the system, instead of moving forward, has regressed in terms of making policy and cleaning up.

So you are admitting that you too were a victim. You said 'some of us' and not the governor alone ...

No, I don't think I said that.

I had in mind certain things I wanted to accomplish as a central banker.

I had my diagnosis of what was ailing the Indian financial sector.

It has always been that it is not just the state of the banking sector but also fiscal arithmetic that is playing a critical role.

I had to take a call on what the best way was to raise these messages on the right platform for an open debate.

If we had to move ahead with financial stability, given the resistance that we had put up -- and clearly if you need institutional reform on the fiscal side -- it requires a significant public debate, which is not going to happen overnight.

So, I had to ask myself what the best role I could play and where.

And, of course, I had to factor in my personal circumstances.

It started with D Subbarao, and then Raghuram Rajan, Y V Reddy, and finally Patel and you. Indian central bankers have started writing books after laying down office. Of course, each book is different.

While Reddy's is an autobiography, Subbarao and Patel have focused on their tenures, and Rajan and you have compiled the speeches given during your stints, with a preface.

Why do all of you decide to do this? To vent your frustrations, which you couldn't while in office?

I would not say it is a way to vent our frustrations.

Most of us are reasonable people in the sense that we expected there would be resistance to what we were trying to accomplish.

It is not easy anywhere in the world to be a gatekeeper of financial stability.

What has changed over the last two-three decades is that initially you know India was essentially a nationalised country.

For all practical purposes, even though government deficits were large, they were being funded through the financial repression of our banks by means of an extraordinary high statutory liquidity ratio.

It was easy for the RBI to guarantee financial stability because you could just engage in financial repression and the private sector didn't own much asset, either.

Securing financial and macroeconomic stability required we move away from these things.

Looking at the friction over time, what is coming home to me is that the central bank is ahead of the curve -- ahead of the rest of the system in terms of securing the foundations of financial stability we need for long-term growth.

The government and the bureaucracy continue with what is suitable for a more nationalised economy of the past.

They are not yet embracing the migration to a market-based economy as substantially and as fully as we might have liked.

You came as deputy governor in charge of monetary policy but your sole focus was cleaning up the banks's books. How did that happen? It was a mandate from the governor or your own choice?

A good question. This is, in some sense, my expertise.

This is what my research is all about: What conditions does a financial sector need to provide healthy intermediation to the economy?

I had studied this in the context of public sector banks in India and how Europe has responded.

Patel perhaps had these issues in his term as deputy governor.

Deputy Governor (N S) Viswanathan played a very central role; he was the pillar of the foundations we were trying to put in for financial stability.

The central theme of your book is fiscal dominance and how it is affecting the banking system. Is it something unique? Isn't that the story the world over?

You are spot on. What that observation reveals is that when growth is slow, governments -- and governments all over the world have myopic horizons -- think short-term.

They try to do the quick thing, which is to get credit flowing, and create a credit-based consumption stimulus.

And, for that, they start leaning on the central bank to relax the rules.

The reason why these issues are more important in India is we are yet to clean up the banking sector.

Let's get into some of the micro issue that you have raised in the book. You have said even the monetary policy committee is under pressure from the government for easing the policy. And, protecting the balance sheets of public sector banks is RBI's responsibility. Tell us a little more.

The details are not important. Tomorrow it may happen in some other form.

Pressure is pervasive. It is not that just one aspect of central banking policy is under pressure.

I would highlight when pressure is on the monetary policy front, it is a lot easier for those applying the pressure to get away with it because now there is an institutional framework under which the MPC has to function.

Some other areas don't have this institutional fabric.

If you ask me to explain why we took a particular decision or why we relaxed accounting rules in the middle of the year, I would say it is because of the public sector banks...

The government is trying to keep the recapitalisation bill down; they have a tendency to come up with intrusive issues such as how to account for mark-to-market gains or when to recognise losses.

These quarter-end things I mentioned in my book are some of the most glaring interventions ... Why should accounting for bank balance sheets change mid-year?

This is because you want to show a particular kind of numbers.