'What you predict depends on the initial data that you input to your model. If initial values (observations) are incorrect, errors add up and forecast results are wrong.'

'We are very serious in our quest to reduce the initial value errors.'

'To do that, we are augmenting our network of rain gauges and observation stations, and plan to have one observation every 25x25 km.'

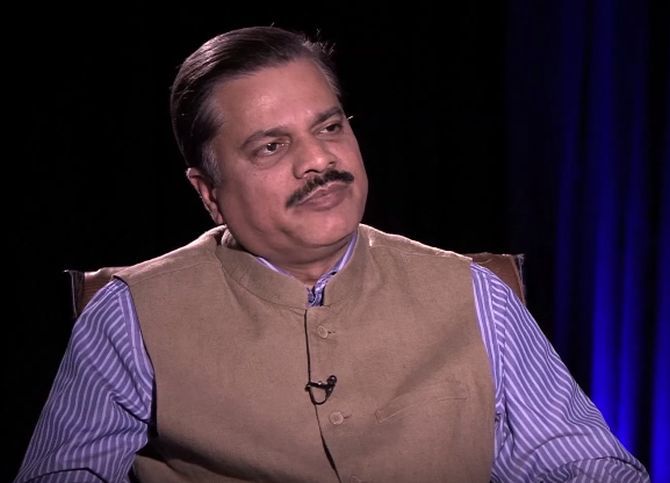

Image used for representational purpose. Photograph: Courtesy, Pixabay

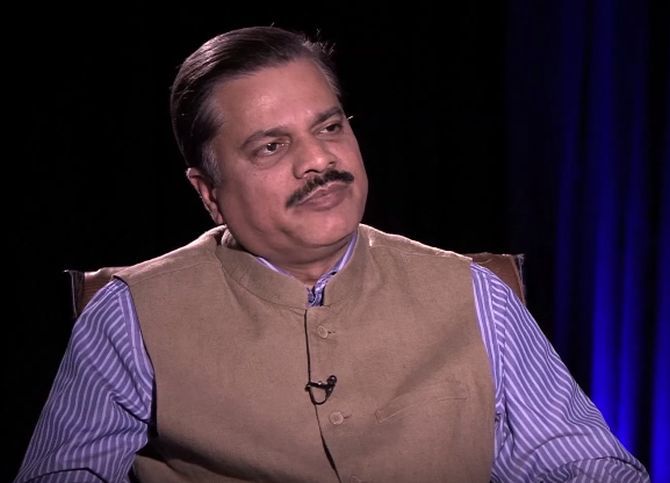

Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, 54, popularly known as the Cyclone Man of India, has assumed the top job at the India Meteorological Department as the director general of meteorology.

Hailing from a coastal Odisha village and having observed numerous cyclones in his lifetime as a specialist, Mohapatra, below, speaks to Abhishek Waghmare as he aims to become an able generalist and be an "institution builder" at the met department as he sets his goals for his term till 2024.

How do you look at this year's monsoon, especially in the context of climate change?

This year, though the monsoon started late, it sprung back to normal, courtesy better-than-normal rains in July.

The El-Nino conditions prevailing in the beginning of June have weaned out, and the outlook looks normal till September, as other major indicators are in the positive.

In the longer term, India's monsoon is going through an epochal trough: a three-decade period where rainfall falls below normal quite frequently. But a bigger worry is the intra-seasonal variability.

Meaning, the extreme events?

Yes, the number of effective rainy days has reduced in consonance with rise in heavy rainfall days.

Some areas in Mumbai clocked more than 30 cm a day twice this season.

If it is not raining, it is not raining at all, and if it is raining, it is raining heavily. This is a fresh challenge.

Image: Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, director general of Indian meteorological department.

The biggest casualty of this are farmers. How do you plan to tackle the problem?

The quality of our forecasts has been improving. We give impact-based forecast in all districts now.

From 3 million farmers under our SMS advisory system, we have come to 41 million now. We plan to reach 90 million farmers by 2024.

In addition, we will transform the static crop calendar to a dynamic crop calendar at the district level (which will take into account the changing climatic conditions to give suggestions on sowing time and the variety of crops).

Climatology as well as crop pattern vary across districts. We will give advisories based on the type of crop and the stage of growth of crop, which is not done now.

We will also build a decision support system to help farmers make informed decisions on crop selection, water use, fertiliser application.

There have been repeated complaints from the public on the accuracy of forecasts, especially from the urban class. How would you address that?

Compared to five years ago, probability of detection of heavy rainfall event has risen from nearly 40 per cent to 70 per cent now.

We intend to improve it beyond 90 per cent by 2024.

But the critical issue here is the "mesoscale" (spread over a very small area) nature of these rains, where detection becomes difficult.

Heavy rains at one place and drizzle two miles ahead, is a frequently encountered situation. We plan to cover the entire country with Doppler radar network in five years.

It will give us observations every 10 minutes, and we aim to reach the 1-km radius by then.

We are in the process of institutionalising "urban meteorological support" system for our growing cities.

But economic activity is rising, and small towns, villages too need accurate forecast now.

Our Nowcast system is working only in 400 blocks of nearly 7,000 blocks (sub-districts) in the country.

We need to ramp it up to cover all blocks, and all villages would then get accurate information three hours before any extreme event.

What are the real issues in erroneous forecasting?

See, what you predict depends on the initial data that you input to your model. If initial values (observations) are incorrect, errors add up and forecast results are wrong.

We are very serious in our quest to reduce the initial value errors.

To do that, we are augmenting our network of rain gauges and observation stations, and plan to have one observation every 25x25 km.

Coming back to data on monsoon, will you revise the onset and withdrawal dates of monsoon rains for different states and cities?

We are in the process, and an expert panel is looking at extensive research already completed on the topic. If required, we would change it, but it would take time.

On the other hand, we have already made changes to the rainfall climatology, and reduced the normal June-September rainfall by 2 per cent.

What are your other initiatives?

We are working on the "South Asia Flash Flood Guidance Project" where flood forecast on each watershed in the country will be given every six hours, every day.

Within a year, this project will be implemented. This will help minimise losses from extreme flood events like the one happened in Kerala last year.

We are building a Common Alert Protocol, wherein the advisory reaches intended people through all media: TV, SMS, commercial messaging platforms and social media.