'Fiscal purists would quarrel with the idea of selling assets to pay for current expenditure -- such as the payout to farmers and the health insurance programme -- for the obvious reason that the process cannot go on forever.'

'At some point, the list of assets available for sale will run out,' notes T N Ninan.

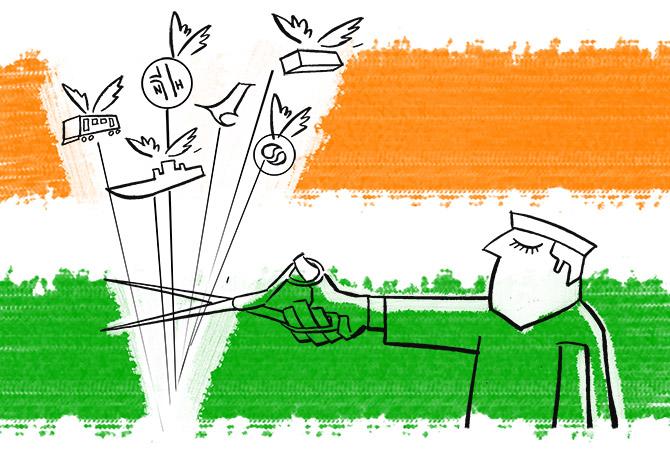

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

The idea of the moment is privatisation.

Railway stations and trains, airports, the Container Corporation, Shipping Corporation, completed highway projects, Air India, Bharat Petroleum -- all of them and more are to be put on the block.

And we are talking not divestment but real privatisation, with change of control -- last delivered by Arun Shourie in the Vajpayee government.

Narendra Damodardas Modi, it would seem, is finally going to act on his stated position that the business of government is not business.

There may be other motivations.

For instance, to rebuild the government's reputation for positive action, since the view has gained ground that the 2016 demonetisation and the flawed goods and services tax have been responsible to some degree for the economic slowdown.

Another objective may be to simply close a widening fiscal gap.

The government has been announcing one new spending programme after another, and one tax giveaway after another. As the bill has got bigger, tax revenue has fallen short. Money has to be found from somewhere, lest the fiscal gap become embarrassing.

The Reserve Bank of India has been made to cough up a one-time transfer, but that won't be enough.

Privatisation could therefore be handy -- except that, with less than half the financial year to go, much of the announced sale of government assets is unlikely to be done by March-end.

Regardless, privatisation is welcome.

Fiscal purists would quarrel with the idea of selling assets to pay for current expenditure -- such as the payout to farmers and the health insurance programme -- for the obvious reason that the process cannot go on forever.

At some point, the list of assets available for sale will run out.

But that is a distant prospect just now, and on the positive side one must reckon on the systemic benefits of a better use of assets in private hands, and/or better service, which is the real logic of privatisation.

Will it work?

Yes, if unlike with Air India the last time round, the government puts out sensible terms for sale or lease.

As for who might buy, it is true that most domestic business houses are still in de-leveraging mode, the focus being on reducing debt.

Also, many established businessmen find their ability to invest badly eroded by bankruptcy proceedings, or by shares pledged against loans being sold at rock-bottom prices.

Anil Ambani, the Ruia brothers, Subhash Chandra and others have all suffered on this account, while Gautam Thapar and the ex-Ranbaxy Singh brothers are among those who have seen a loss of both financial as well as social capital.

On the other hand, corporate de-leveraging over the past few years has reached a point where quite a few companies are sitting on large amounts of cash or have headroom for taking on more debt, but are not investing because of the consumption slowdown.

The chance to enter new businesses or buy quality assets may induce them to open their cheque books.

Besides which, there could be some international interest.

All this comes with political risk.

The RSS chief has sounded a warning on some aspects of policy, and there are stirrings of unrest among trade unions.

The Modi government is strong enough to over-ride such resistance, but it should be aware of reputation risk.

Privatisation in many countries, including India, has come arm-linked with controversy.

The risks get heightened when decisions on complex financial questions about long-term leases are rushed through in a hurry, without mandatory consultations -- something already aired in connection with the lease of airports to the Adani group.

Meanwhile, it is not clear why the focus is on entities in the transport sector.

While the privatisation drive is masterminded by the prime minister's office and the NITI Aayog, it could be that two dynamic ministers are in charge of most of transport: Nitin Gadkari and Piyush Goyal.

But that is no reason for not taking a hard look at the more difficult choices facing State-owned entities in other sectors -- specifically the loss-ridden telecom twins that have no hope of viability, and government banks, which have already swallowed up an unconscionable Rs 2 trillion of taxpayer money in the past five years.