'The fact that Kalanick and others managed to build such great companies, in spite of their apparent foibles, should give us hope,' says Vikram Johri.

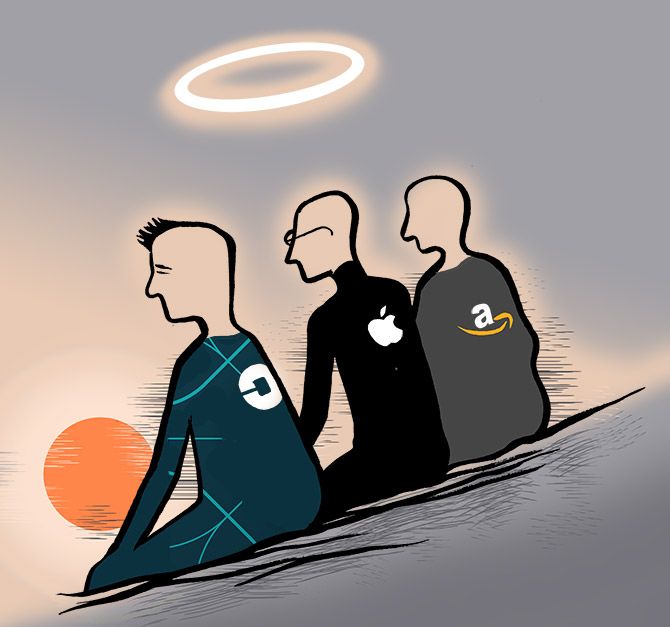

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

The resignation of Uber CEO Travis Kalanick brings to a close an exciting, if fraught, era in the company that revolutionised ride hailing.

So strong is the company's influence that the word 'Uber' has become a buzzword for any on-demand service, from tutors to doctors, that the Internet economy readily allows.

Kalanick was not an easy person to work with, as media accounts leading up to his resignation amply demonstrated.

Most infamously, he got his India team to probe the truth of the rape claim filed by a passenger against an Uber driver in 2015.

There have been other clues to Kalanick's skewed moral moorings throughout his tenure, including overlooking sexual harassment complaints filed on his watch.

Even so, Kalanick's misdemeanours pale in comparison to those of Apple founder Steve Jobs, who, apart from being the boss from hell, denied the paternity of his daughter for many years.

Lisa Brennan Jones, who eventually reconciled with her father, grew up on welfare as her mother made ends meet cleaning houses.

While Kalanick's achievements are not in the same league as those of Jobs, these two men have earned demigod status among fans and foes alike.

Jobs has long been recognised as the man who changed the face of computing by introducing a sleek, design-oriented approach to personal computers, in the process renaming them.

Kalanick, meanwhile, was the first to imagine an idea that seems almost simple-minded in hindsight, yet one whose impact has got the entire automobile industry huffing.

Listen to all the talk of driverless cars.

Jobs' and Kalanick's outsize success contrasts uncomfortably with their less-than-peachy private reputations.

Should we then accept that it takes a certain ruthlessness to succeed at their level?

I am not referring to garden-variety ruthlessness here, the kind where you plot to get that much-desired promotion or flatter the boss for a suitable appraisal.

I am talking about the sort of deviousness that tips into morally murky territory.

It is possible that the single-minded passion needed to bring a revolutionary idea to fruition also dehumanised these men, so that they could take dubious calls on ethical matters with as much ease as they signed off on corporate decisions.

If we were to take this correlation seriously, we must ask if their efforts were, in the final analysis, worth it.

Taking a purely utilitarian view, it would be tempting to say that Apple and Uber have done much good for the many even if their progenitors brought untold harm to some individuals.

The trouble with this narrative, apart from its dubious moral underpinnings, is that it does not sit easily with the inspirational spiel that the stories of our corporate leaders are supposed to provide.

Jobs' 2005 graduation speech at Stanford, a viral hit on the Internet, hits the sweet spot with moving stories of his adoption and his firing from Apple. But a fuller knowledge of his personality makes it difficult to visualise him as a role model.

The moral lines can also be hazy.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos was raised by an adoptive father, and his own never made an effort to reach out to him.

The father and son were not in touch and it was journalist Brad Stone who, while researching a book on Bezos, came across Ted Jorgensen in 2012 and told him about his link to the chairman of the world's most powerful retail company.

Jorgensen, who passed away in 2015, expressed a desire to reconnect with his son, but Bezos did not oblige.

Bezos' case introduces us to the limits of weighing in uncomfortable personal details while divining leadership, and in our demanding age, spiritual lessons from our greatest corporate leaders.

With the biological father staying away, Bezos' relationship with Jorgensen was damaged beyond repair, and while we may prefer if Bezos had charitably acceded to the dying man's wish, we cannot be too certain of our moral outrage at his refusal to do so.

For some reason, it is easier to empathise with Bezos than it is to appreciate the reasoning that drove Jobs and Kalanick to behave the way they did with their employees/family.

That may be an outcome of our desire to apportion blame and ascertain who gained what and who was the wronged party, ultimately.

But even in today's media-saturated world, it is impossible to know the entire truth of any life, and it would be prudent not to bracket these men so easily into slots of right and wrong.

Truth be told, it is somewhat childish to expect our leaders to have made the best, the most morally salient decisions during every personal or professional crisis that ever hit them.

If anything, the fact that Kalanick and others managed to build such great companies, in spite of their apparent foibles, should give us hope.

Far better to appreciate the complexity of human undertaking than to hanker after envisioning all the good of the world in those who have succeeded, even if spectacularly, in one field.