Ramdev's Patanjali is a low-cost, low-margin business that gets away with pretty much what it wants because wily old Ramdev knows how to get around all politicians, says Vir Sanghvi.

The swami as conman is a familiar theme.

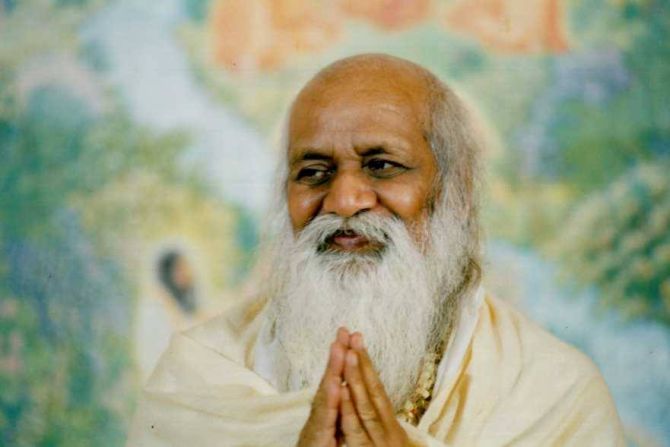

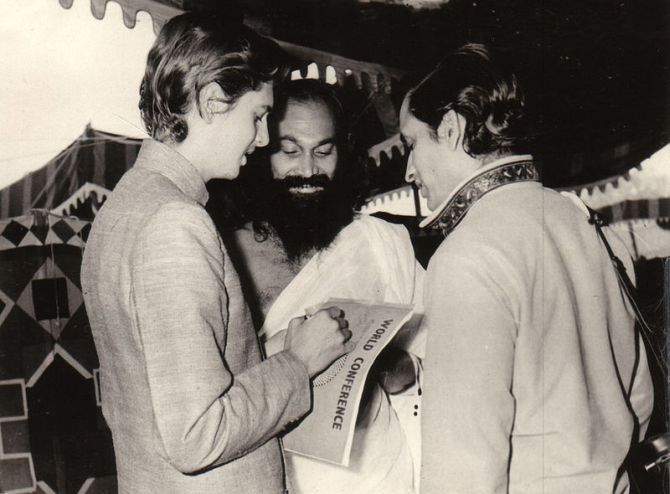

When Maharishi Mahesh Yogi attracted such pop stars as the Beatles and Donovan and movie stars like Mia Farrow to his ashram, most Indians were delighted. Mahesh Yogi had put India's spiritual tradition on the world map, we said.

Then, disillusionment set in.

The Beatles stormed out of the Maharishi's ashram, claiming that he had molested one of the foreign celebrity devotees (John Lennon later suggested that this was Mia Farrow).

Despite the swami's apparent love of worldly pursuits, nobody doubted that he knew his yoga.

Transcendental meditation, the technique he introduced to the West, has outlasted him.

Similarly, most people reckoned that Dhirendra Brahmachari, Indira Gandhi's favourite yogi, knew his stuff. How else could he stride through the streets of Moscow at the height of winter wearing nothing but a thin muslin wrap?

The problem was that the Brahmachari seemed more interested in peddling influence and acquiring land than in yoga. His nickname was the Rasputin of Delhi.

But there is something about prime ministers and yogis.

By the time Chandra Shekhar became prime minister of India in 1990, Chandraswami had already been exposed as a crook called Nemi Chand Jain who had faced criminal charges before declaring, one day, that he was a swami.

He had been involved in a sordid corporate battle between Mohamed Al Fayed and Tiny Rowland in London, had been thrown out by the sultan of Brunei and investigated by Indian authorities for forging documents relating to a St Kitts bank account in the name of V P Singh's family.

No matter. Chandra Shekhar clutched the swami close to his bosom and even gave him the authority to settle the Babri Masjid dispute.

You could argue that Chandra Shekhar was an aberration, a short-term prime minister, propped up by others.

But what of Narasimha Rao, great reformer, father of today's entrepreneurial India and so on?

Chandraswami was so close to Narasimha Rao that he performed (possibly tantric) havans at the prime ministerial residential complex. He continued to steer businessmen towards the prime minister and Rao never felt the need to throw out this obvious charlatan.

Many of these swamis became millionaires.

Mahesh Yogi's empire was worth many millions by the time he died (though he claimed that none of the money was personal wealth).

Dhirendra Brahmachari owned large swathes of property.

And, at one stage, Chandraswami had so much money stashed abroad that he kept the Saudi arms-dealer and playboy Adnan Khashoggi afloat (Bad decision! Khashoggi spent all the money, causing a huge dent in the swami's fortune).

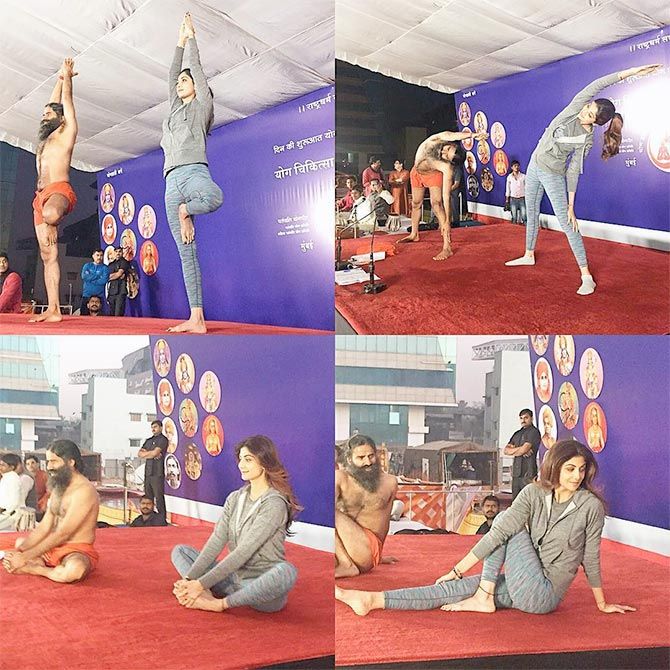

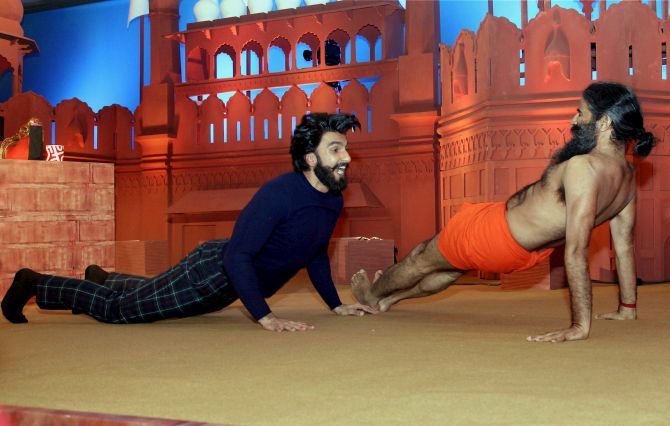

Today's millionaire swami is Baba Ramdev, he of the wobbling stomach and the hearty laugh.

Ramdev, of course, is above such trifles as money but his partner/companion Acharya Balkrishna, in whose name all the businesses are, is worth Rs 25,600 crore (or $3.8 billion). At that level of wealth, Chandraswami seems like a pauper in comparison.

But Ramdev is different from his predecessors. Most of them made their money from their closeness to the powerful and the mighty.

Ramdev is no slouch when it comes to establishing close relations with chief ministers and other influential politicians but his wealth has two, largely legitimate, sources.

The first is the religious TV network that turned him, in the manner of an American televangelist, into a national figure.

The other is his fast moving consumer good company. Its turnover was Rs 10,000 crore in the year ended May 2017. By the next year, Ramdev has declared he hopes to reach a suitably spiritual Rs 20,000 crore.

As he put it, with his characteristic subtlety, 'Pantene ka toh pant gila hone wala hai. (Pantene is going to wet its pants).' 'Colgate ka gate bhi bandh hoga... (Colgate will run out of business)'... there was a dismissive line about each of his competitors).

Three questions strike the average person.

First of all, who is this guy?

According to Godman To Tycoon: The Untold Story Of Baba Ramdev by Priyanka Pathak-Narain, a carefully written and well-sourced biography, Ramdev was a sickly, partly facially paralysed (that explains the twitch in his eye) son of a Haryana farmer who met his future partner Balkrishna (described cruelly in the book as 'a young man with a high pitched voice and protruding teeth') when he was in his late teens (we can't be sure about age because Ramdev won't tell us when he was really born) and the two of them hit the swami-yogi circuit.

Ramdev ended up in a gurukul where he routinely beat his students; one of them was assaulted for so long that 'he was left in a critical condition. The boy's body was in shreds, blood flowing freely from his wounds.'

Ramdev hotfooted it out of the gurukul and rose to become a reasonably well-known swami who cultivated such chief ministers as N D Tiwari and Mulayam Singh Yadav.

The second question: How did this guy get to be so big? Short answer: Television.

In the 21st century, a new middle class that looked to TV for spiritual guidance gave him the kind of adulation that would have made Shah Rukh Khan, let alone Jerry Falwell, jealous.

Three: Why are his products so successful?

Well, because he uses his TV channel to promote them at no extra cost; because they fit in nicely with the back-to-Hindutva mood of the times and because, as this book points out, he sells most of them cheap.

The book suggests that he does this by cutting corners.

His workers are paid much less than the industry standard. Forget about trade union protests, Ramdev's workers consent meekly to having their mobile phones confiscated at the entrance to his plant.

His labelling can be misleading: As the author points out his desi ghee is no such thing; his products may use animal parts that are not declared on the label and sometimes he launches new goods (noodles, for instance) without bothering about the necessary approvals.

His is a low-cost, low-margin business that gets away with pretty much what it wants because wily old Ramdev knows how to get around all politicians.

Manmohan Singh gave him legitimacy by meeting him to discuss the cleaning of the Ganga and, when he threatened to launch an anti-corruption agitation, the UPA sent four senior Cabinet ministers (including Pranab Mukherjee!) to receive him at the airport.

He is on cosy terms with the current Bharatiya Janata Party leadership and its focus on yoga allows Ramdev to turn himself into the mascot of such campaigns.

Can all this last?

Are the big FMCG companies really going to wet their pants, as Ramdev claims?

This book is non-committal. But my guess is: Yes. Ramdev is a symbol (or a symptom: Take your pick) of today's India.