The Licence Raj did not always mean that there was no competition - in the seventies there were half-a-dozen two-wheeler manufacturers - Ideal Java, Enfield, Rajdoot of Escorts and Lambretta - slugging it out.

It was the early seventies and the heydays of the Licence Raj.

I was just 35 years old but as chairman and managing director of Bajaj Auto, I was summoned by the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Commission. My "crime"?

I had produced more scooters than what was permitted under my industrial licence.

The rules stipulated that a company could produce only up to 25 per cent in excess of its licensed capacity.

I went to Delhi to face the three-member commission in New Delhi without a lawyer. M A Chidambaram, chairman of Automobile Products of India (API), which manufactured Lambretta scooters, had been invited as a competitor.

He tried to show that his scooter was superior by saying it weighed about 100 kg and that the Bajaj (then Vespa) scooter weighed only 94 kg.

I replied, "Yes, the Lambretta scooter is 100 kg of silver, the Bajaj scooter is 94 kg of gold!"

The hearing was a success. Not only did the members allow Bajaj Auto its expansion but their report also complimented me for my knowledge and command of the facts and figures of the case.

.jpg?w=670&h=900)

The commission report also mentioned that though there was a premium on Bajaj scooters in the open market and demand exceeded supply, our scooters were the cheapest.

The Licence Raj years were difficult and disastrous for the country.

I used to spend my time in the corridors of Udyog Bhavan instead of the factory, and became friends with many in the Directorate General of Technical Development, including even the section officer, H C Sharma. It was not easy to get an industrial licence either, because political equations mattered.

Bajaj Auto, for instance, was pipped to the post in 1958 for the first industrial licence to make scooters and three-wheelers by the Chennai-based M A Chidambaram. T T Krishnamachari, who was industry minister then, called up Chidambaram, who was then a Bajaj dealer, to tie up with the Italian two-wheeler manufacturer of Lambretta scooters.

We had made an application for collaboration with Piaggio, manufacturers of Vespa.

A few months later I got the bad news - Chidambaram had been given the licence and there was no more capacity available! Bajaj had to wait two years for its turn.

The Licence Raj did not always mean that there was no competition - in the seventies there were half-a-dozen two-wheeler manufacturers - Ideal Java, Enfield, Rajdoot of Escorts and Lambretta - slugging it out.

However, only Bajaj Auto's products had a 10-year waiting period. We faced competition, but I focused on three things: cost, quality and volumes.

Others failed to do so and they could not compete with us on quality or price. Of course, I was always under pressure from workers, dealers and vendors to raise scooter prices and share the higher margins but I refused.

The shortage regime meant they were making money.

The market premium of the quota regime, apart from customers, went to a few dealers and brokers who made a killing by first booking their orders and then selling scooters in the black when their turn came.

Retrospectively, we should have seen the switch within the two-wheeler market from scooters to motorcycles in 1999-2000. In 2001, I had no hesitation in saying that the year under review was a very bad year for Bajaj Auto even though the company's profit after tax, though lower than before, was higher than competitors.

But as early as 1986, I had signed a technical collaboration agreement with Kawasaki of Japan.

What happened was that Kawasaki, Yamaha and Suzuki all had two-stroke engines on their motorcycles.

Only Honda had four-stroke engines. Other things being equal, a four-stroke engine is more fuel efficient than a two-stroke one and this was the advantage Hero Honda enjoyed over the three other motorcycle manufacturers in India.

Our problem was that Honda wanted equity in the Indian company and we only wanted a technical collaboration agreement.

That is why we went with Kawasaki, which, like us, wanted only a technical collaboration agreement. But even though the market was changing Bajaj scooters continued to sell well till about 2000, though the waiting periods vanished and the decision to stop production of scooters was taken only in 2009.

By 2000 my son, Rajiv, who joined the company in 1990 and started taking major decisions in the company, built a team in our R&D department to start work on producing a new motorcycle.

It naturally took some time, but when we developed and marketed the Pulsar, it became an outstanding hit in what is called the sports/high-end category.

Also, from 2007 onwards when Rajiv took charge of exports as well, he substantially expanded our overseas sales.

Currently, Bajaj Auto exports about 30 per cent of its motorcycles and over 60 per cent of its three-wheelers.

I believe, however, that a company has to be a leader in its domestic market as well if it has to sustain the growth of its exports.

Although I am very happy with Bajaj Auto's export performance, I am concerned that not only the Chinese but the Japanese may catch up in the markets where Bajaj Auto is currently a leader.

Although I appreciated Rajiv's decision to concentrate on motorcycles in the early 2000s when the Indian market was changing, I differ with him in that I believe the company should re-enter the scooter market now with a gearless scooter, which can capture a good market share.

Overall, I think economic liberalisation was good for India and I said so in speeches at various industry associations at the time.

But somehow, I was labelled the chief spokesman of the so-called "Bombay Club" in the nineties.

This is a misunderstanding. Some 14 industrialists (including Ashok Jain of Bennett, Coleman and Company and Hari Shankar Singhania of JK) met at the Belvedere Club in Oberoi Hotel in Mumbai and finalised a representation to the finance minister for a level playing field after import duties were satisfactorily reduced.

Our point was simple: most consumer goods came from the developed world that did not have our handicaps like rigid labour laws, high interest rates, poor infrastructure and so on.

So we were being made non-competitive. But all the others kept quiet after the finance ministry asked them not to go public after they made their representation - except me.

The simple economics of Adam Smith teaches us that everyone cannot make everything, so we must decide what we want to manufacture and adjust import duties accordingly. We were not saying anything new.

We were saying choose items you want to make in India and give us flexibility. For the rest, the government can reduce import duty. In fact, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is saying the same thing - "Make in India".

The developed world is protectionist when it suits them - for example, when it protects its farmers. And, in fact, despite my "Bombay Club" label, I was the one who, from 1979, brought India to the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos and brought the WEF to India!

In the late nineties, we considered the possibility of entering the passenger-car market, negotiated with a few American and Japanese manufacturers and almost finalised a joint venture with Chrysler.

However, our investigations during this period and the performance of the other car manufacturers in India made us realise that in terms of marketing and branding it was not the correct decision for Bajaj Auto, which was and is known as a two- and three-wheeler manufacturer.

We did consider making a small car jointly with Renault, but Rajiv decided to make a quadricycle, which Renault did not want, so the collaboration did not materialise. Personally, I think the quadricycle may not succeed as a private passenger vehicle since the Indian consumer has become aspirational - after all, even the Nano did not succeed.

However, it will be an excellent replacement for the three-wheeler autorickshaw since permits for them will gradually be issued in smaller numbers.

What I found truly surprising, however, is that many industrialists who supposedly favoured liberalisation and criticised the "Bombay Club" were the very ones who strongly lobbied against Bajaj Auto's quadricycle, which has been allowed to be sold as a commercial vehicle from October 1, 2014.

These automotive companies were afraid of competition and made wrong accusations on grounds of safety.

They could not explain how a four-wheeler quadricycle is more risky than a three-wheeler that is freely allowed to run on Indian roads.

They also wanted the government to delay giving Bajaj Auto permission to introduce its quadricycle in the market so that they could produce a similar vehicle. Obviously, their arguments regarding safety were false.

And they did not believe in competition when they thought it would hurt their interests!

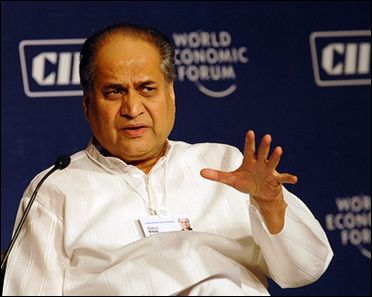

(Rahul Bajaj is Chairman, Bajaj Auto)