'There is economic danger: Not inflation, but a slowdown that feeds an employment crisis,' says T N Ninan.

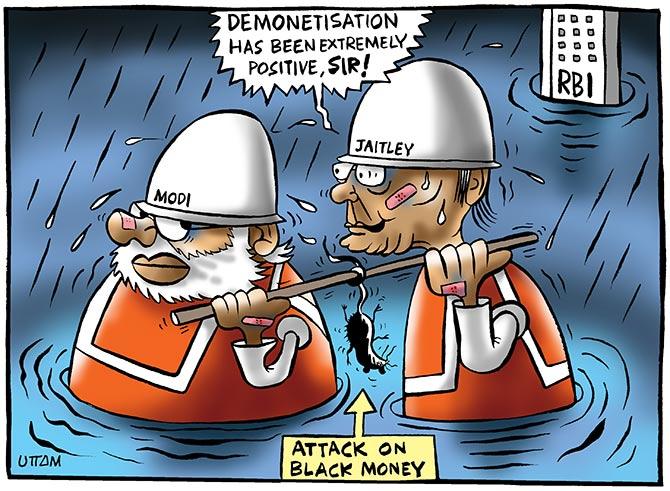

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

There is a paradox at work.

The Modi government gains in political strength and popular support even as the economy swings downward.

Can the two continue to move in opposite directions?

For a while, certainly. Indira Gandhi remained hugely popular for many years even as the economy slipped into its lowest growth phase since Independence.

What helped her was that she sold people the dream of removing poverty, and took a number of populist steps: Nationalising banks and giving below-cost loans to the poor; and raising income tax rates to 97 per cent in a Robin Hood scenario of taking from the rich and giving to the poor.

She also won a war and carved up Pakistan, even as she built a personality cult.

Are there parallels with today? Yes and no.

Majoritarian nationalism is the current zeitgeist, more resilient than the old promise of Garibi Hatao, which depended on performance.

The narrative of taking on the corrupt rich has been re-invented through demonetisation -- something that high income tax rates did back then.

The current writing off of bank loans for farmers compares with below-cost bank loans then, even as Jan Dhan today mimics the bank reach-out done after nationalisation.

Doklam is not comparable to victory in the Bangladesh war, but it has fed the narrative of a strong Narendra Modi standing up to the Chinese.

Finally, there is the same personalisation of politics.

Two things upset the applecart for Indira Gandhi: The spread of the then unfamiliar stench of corruption, and the double-whammy of an oil price shock combined with successive drought years, which caused runaway inflation.

In the face of political and economic disaffection, she turned authoritarian.

Today, Mr Modi's corruption-fighting narrative still holds and indeed gets buttressed, but there is economic danger: Not inflation, but a slowdown that feeds an employment crisis.

The criticism of demonetisation leads to the broader charge of economic mismanagement, following two quarters of poor GDP numbers.

But without a matching political narrative, Mr Modi faces no real threat in 2019 -- unless, even in a progressively Opposition-mukt polity, his and his cohorts' incipient authoritarianism and street thuggery turn people off.

The economy needs a boost, but what we have is a financial storm brewing in the form of bank loans that cannot be repaid.

Growth needs credit, which is stagnant. And rapid growth requires exports to pick up, but the rupee's exaggerated value does not help.

Investment needs to recover, but the Reserve Bank misjudges growth prospects (7.3 per cent this year, it says) as badly as it did inflation, and keeps interest rates too high.

Factor markets (land, labour, capital) have not been reformed, so the conditions are yet to be created for a real estate revival or for 'making in India'.

The skills programme will work only if it is tied to apprenticeship -- no one will pay for acquiring a skill if there is no job at the end of the rainbow.

The management of cities and towns cries out for reform.

That the employment guarantee programme now needs additional outlays is comment enough on the jobs front.

The prime minister must know that, two-thirds of the way into the life of his government, he is at a crucial juncture.

Luckily for him the original promise of scaling up to double-digit economic growth has faded from public memory, but the government's programmes have to work so that Mr Modi gets his talking points.

He has quite a few: Macro-economic stability, major tax reform, success with renewable energy, more highways built, the virtual abolition of petroleum subsidies, and so on.

But the problematic outcome of, or poor progress on, many initiatives also figures: Uday, crop insurance, Swachh Bharat, halving the share of imports in defence orders, cleaning the Ganga, safe travel on the railways ...

The ministerial reshuffle comes at the right time, but most of the ministers in this government have been strictly peripheral to the main action.

It all comes back to Mr Modi, who as always scores high on effort but is now slipping on the results front.