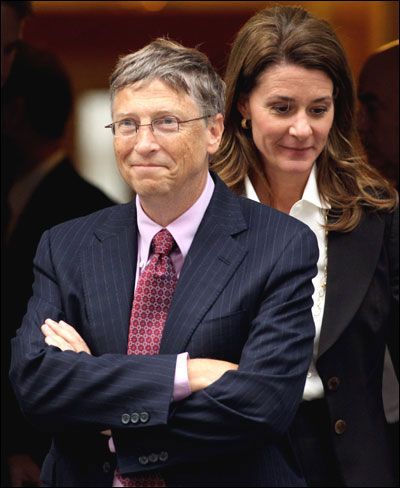

On a recent visit to India, Bill and Melinda Gates spoke with the author Chetan Bhagat about the philosophy behind their philanthropy at a public event titled "All Lives have Equal Value" on September 18 in New Delhi.

They are co-chairs of the Gates Foundation, which has directed $1.4 billion at health (including HIV and polio prevention) sanitation and maternal mortality in India over the past decade. Excerpts:

Chetan: Welcome to India, Bill and Melinda. I'm very nervous. This is a huge honour for me and I'm a big fan.

"All Lives Have Equal Value": they told me that this was the session's title. So, just want to ask both of you what made you arrive at this mission? What does this mean to you?

Melinda: This is a personal belief that Bill and I have.

All lives do have equal value, but as we looked at what was going on around the world and as we started to learn more about what was going on in Africa or India, we (realised we) don't treat all lives as if they have equal value and we should. So, it's become the mission of our foundation and it will be our life's work.

Chetan: Bill, you generated wealth and you decided to open a foundation to do good for the society. You were an entrepreneur and now are a philanthropist.

You could have perhaps opened another company, which did good for the society like a renewable energy company, a pharma research company. Instead you chose this complete U-turn from the entrepreneurial path (to) this foundation. How did it all happen?

Bill: Microsoft had a chance - by being at the very beginning of the computer revolution - to have this huge impact. For the philanthropy, we wanted also to have big impact, a kind of a new dimension. And what we saw was that for the diseases and challenges affecting the poorest, nobody was really bringing in the best scientists and the best measurement techniques.

So whether it was tuberculosis, malaria or a variety of diseases, they were just neglected and it wasn't clear who was supposed to step up.

Yet the poor countries who have the problems were never going to organise the capital and the scientific discovery process in a way that would get rid of these problems.

You know, people will ask me about Microsoft. They say 'Well, are you an entrepreneur?' I say 'No, I didn't think that way when I started a company.' I fell in love with software and it turns out… you want to get software out in the world, you build a company. So I started with the love of software first.

Here at the foundation, it was this love of innovation on behalf of the poorest, in building an institution that hired scientists and built partnerships.

But I don't have any idea if the private field would have had nearly the same impact that the foundation has had.

Melinda: I think it's also important to say that, you know, right after Bill and I were engaged and even before that, we were talking about the fact that the resources that we were amassing from Microsoft would go back to society.

We read an article about something called Rotavirus in The New York Times, which is a diarrhoeal disease killing over a million children, and we were kind of scratching our heads saying, 'How can that be?' If a child in the US gets a diarrhoeal disease, you go down to the drug store and you get an off-the-shelf product. What is the failure that's happened that allowed so many children to die of that disease?

Then it became a learning journey to learn about so many other diseases and learn what were childhood deaths, etc that then led us to all the various places we have now gone with the foundation.

Chetan: Which brings me to again link that to this classic capitalist/socialist argument. Doesn't welfare create dependencies… doesn't it get the government off the hook?

Bill: Well, first on capitalism versus socialism, the system that works is largely a capitalistic system; no one really believes in 100 per cent capitalism.

You can't run a police force or a judiciary capitalistically and even in domains like food, you can't be capitalistic.

You need food standards, you need laws to make sure the pricing is done in a fair way.

You need to fund research that the private sector tends not to do, but the basic research has actually driven a lot of the advances forward. And so you want the market to extend pretty far.

Different countries draw the boundary differently. The more socialistic things are, the less you get this incentive system and measurement system that works fairly well.

There are certainly some areas where India still has a history of a more socialistic approach that will over time have to change to unleash all kinds of innovation.

The area we work in primary health care isn't a market, i.e. making sure every kid has vaccines, making sure delivery for services are available for women.

The government has got to make sure those are offered. Now, you could outsource it to NGOs or even for-profit companies but by and large, the government has chosen to do this itself.

We don't want to take credit for something where basically in all of our programmes, we are partners with the government - or actually, our partners are partners with the government.

Helping them get smarter faster: How do they train their people, what tool should they use, how do they take the best practices from other parts of the country or other parts of the world and apply those.

And in the long run, the basic responsibility for making sure every child gets vaccines or safe delivery, that's with government.

And if we have been able to be in there and help them do that with high quality and high efficiency, the dream and the belief is that it will stick when we can move on and work on something else.

Chetan: We have seen a change in government, there is Mr Modi who is in power, broadly do you think it's a progressive agenda, do you see hope, do you see it's really something that could change things in India?

Melinda: We were enthused about the government that's come to power.

I think in a couple of areas specifically that we working in: health, for instance - the fact that they came out right away and said that they are going to roll out four key new vaccines across India.

That's absolutely huge. That will bring down childhood death.

Childhood death under five has been coming down since 1990. It used to be 12 children died out of every 100 born (in India).

Now, we are down to five children dying out of every 100 born, but if you want to still get that 1.4 million children that die every year, you got to roll out these key vaccines and some of these are very specific to India like Japanese encephalitis.

We see the commitment to newborn health, the fact that half the children that die are newborns.

Huge commitment to that, huge commitment to getting out sanitation, which again will ultimately bring down diarrhoeal diseases and also make sure that people get the right nutrition to grow up healthy and be able to contribute and be part of the society and in school.

So, just those three things alone we're really excited about.

Bill: I'd say there are a few things that are still unclear. When push comes to shove (on India's) health budget, it's going to have to go up.

This government really needs to figure out the fiscal balance, so it will be interesting to see if that's going up.

I also think for the economy as a whole, there's some unpopular things that need to be done. The real test of a government is are they willing to do things that are good for the country? What good is a mandate if it's not to do some unpopular things?

In terms of our particular priorities, some great goals have been set. We're very enthused and we need to see… actual execution, the quality of implementation, the quality of the bank accounts - do they get used. There is a lot to be done there.

Chetan: You have chosen to take a path in life where you see suffering on a daily basis. Does it have a toll?

Can you give an example where you are so moved that you just get overwhelmed and forgot about the foundation and just as a human being you couldn't take it.

Melinda: Sure. You see unbelievable things in the slums in Delhi, and I think it's important to take those things in and to not forget them, as tragic as they are and as heartbreaking as they are.

They also move you to action.

I will give you one example from when I was in UP years ago. I was walking to a village and stopped by a woman's house.

She didn't know who I was, where exactly I was from in the west. She begged me to take two children home. What she said to me is: 'Can't you see, I have nothing? My husband is hurt. He was injured on the job (and he was there lying on a mattress).

We have no land, we have nothing, and I have five children, I can't feed these children, will you take two home?' That's heartbreaking, right, I mean absolutely heartbreaking and you'd like to take that child home. But what spurs you on is to say: 'How many families are in that situation and what can we do on a much larger scale to help lift people out of that abject poverty, so that they are not asking (people) to take their children home.'

No mother ever wants to be in that situation.

Bill: Yeah, I think the two most emotionally tough times I had during work with foundation were both here in India and they had to do with this effort called Avahan, which was about reducing HIV infection.

It was decided by the foundation team here that in order to do that you had to create communities for the sex workers where they could talk to each other and share stories and figure out how to stop police exploitation and violence and so many awful things that they have to put up with.

And so, we gathered the members of these communities together and one woman talked about her child who was ashamed of her mother and had committed suicide. It was the most horrific tale I have ever heard.

There were several very tough ones just to listen what it was like, how people ended up in the situation, what their hopes were, how they were still wanting to get on with life and do good things.

Chetan: You are husband and wife and you are colleagues too. So, I'm going to ask you to performance review him, a very mini one, one strength one area which he has done well and one area for improvement.

Melinda: One huge area of strength I'd say about Bill is his unbelievable curiosity. No matter what the topic is, he is so interested, his curiosity is so focused on doing the right thing for the poor.

And the one area for improvement is Bill is very tough on himself and sometimes he can be tough on other people.

Not tough on them personally, but tough on 'Do you really know.' So, if you were here presenting the results of Avahan, he is going to go through all the results with you and if you really don't know them, he's going to be tough on you. That was true at Microsoft too, but that's also what makes progress.

But his toughness is also toughness on himself.

Chetan: All my questions okay so far?

Bill: Sure.

Melinda: Oh we are still going to go home together tonight after this...

Chetan: (To Bill) Your turn, all yours.

Bill: Well, Melinda is great about the people dynamics, how the processes we are using and the various personalities are coming together to create, to let people do their best work.

She'll often look at choices we have through that lens and find allies inside the foundation who can help her improve those things.

It makes a huge difference to have us always thinking about that and being part of how we make decisions.

Yeah, in terms of negatives… you know she doesn't like long memos.

Melinda: Everything is binders of information, like you get a 50-page memo.

Chetan: He is giving the feedback.

Melinda: Sorry, let's see how this works.

Chetan: Bill, in one of your earlier interviews I saw, someone asked you to make a pitch for giving and you said it very simply.

You said, "You can't take it away, it's not good for your kids, so I might as well give it away…"

Bill: Well, first generation fortunes don't believe in aristocracy, they don't believe in dynasties. Once the fortunes get passed down in a dynasty it's little hard to stop because it's like 'Well, Dad gave it to me.

Who am I to stop this': Warren Buffett (likened it to) an Olympic team picked (from) the grandchildren of an Olympic team from 60 years ago.

You just wouldn't do it that way and yet in terms of wealth and deciding how wealth gets allocated, there is a little bit of that goes on. So societies adopt the state taxes that encourage people to be philanthropic because they make that a special case.

I think the trend will be in favour of more philanthropy even in cases where the fortunes have been passed along.

Melinda: There is also an amazing sense of empowerment if you can earn your money.

We both grew up in very middle class families. F

or me, in my twenties to know I could sustain myself and actually sustain a family whether I married Bill or somebody else. That's an amazing feeling.

I went to school with some kids for whom, you know, the wealth had been passed down three to four generations. There is a sense of entitlement that comes with that and that I don't really think you want (that) in your society.