'The Indian economy is in slowdown and growth may stay slow,' notes Devangshu Datta.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

The US Federal Reserve has an optimistic forecast for 2020, saying moderate GDP growth and low inflation are likely in 2020.

After three rate cuts in 2019, the Fed intends to hold rates steady in 2020, unless there's 'material change'.

The European Central Bank has also held policy rates for refinancing, marginal lending, and deposit unchanged. >The ECB deposit rate stays negative.

The Bank of Japan is expected to continue with an ongoing Quantitative Easing and to keep policy rates negative.

The high probability of Brexit makes it likely that more easing could be in store, but there's no change currently in the stance of three major central banks.

All three banks are already committed to easy money.

But there were bets being placed on USD rate cuts, and those bets will not pay off.

Since 2008, when QE became popular, traders have talked about being 'risk-on', and 'risk-off' in attitude.

Risk-on attitude, meaning the willingness to gamble on risky assets (such as Emerging Market equity and debt), coincides with trends of lower (or negative) interest rates and expanding liquidity via monetary measures such as QE.

Risk-off, meaning a retreat to hard currency assets, (safe but low-return government debt for example), occurs if rates are stable or rising, and liquidity is not expected to expand.

The latest central bank policy updates may incline attitudes towards 'risk-off' since more easing was expected in this round.

The latest Indian macro-economic data continues to be disheartening.

The Index of Industrial Production contracted in October, for the third month in succession.

To some extent, this is due to the festive season -- holidays mean lower manufacturing.

But it does suggest manufacturing may not recover in Q3.

Retail inflation spiked to a two-year high of 5.54% in November year-on-year.

Food remains the major driver for the upswing.

Core inflation stayed at 3.5%, much the same as October's 3.44%.

The Purchasing Manager Indices are suggesting expansion in activity, with both Services and Manufacturing PMIs climbing above 50 in November.

Again, this could be partially a festive season effect.

Foreign portfolio investors's attitude may be crucial to sustaining equity valuations.

FPIs have bought over Rs 75,000 crore (Rs 750 billion) of India assets in 2019-2020 (April 1 to December 10) including Rs 46,000 crore (Rs 460 billion) of equity and Rs 24,000 crore (Rs 240 billion) of debt.

S&P's latest statement indicates a possible downgrade of India's sovereign rating if growth does not accelerate.

Given that every reliable indicator suggests the slowdown will continue, with consequent shortfalls in tax collection targets and a higher fiscal feficit, there is a high probability of downgrades.

Moody's has already downgraded to 'Negative' from 'Stable'.

Any further downgrade would push India below investment grade.

This would force some categories of FPIs to quit investing in rupee debt.

It may induce other FPIs to cut India exposure.

Continuing turmoil in the north east and the Kashmir lockdown will not help create positive FPI perceptions either.

Investors should be prepared for such bearish scenarios.

The last fiscal when the FPIs pulled out significant sums was 2015-2016, when the Nifty fell 10% from April 2015 to March 2016.

Balanced against this, there may be no sovereign downgrades if GDP growth doesn't slow further.

Also since the overall stance of central banks remains accommodative, risk-on attitudes may well prevail after the disappointment of the latest policy updates are discounted and absorbed.

Predicting where earnings will go is always difficult and the uncertainty is higher than normal for 2020.

The Indian economy is in slowdown and growth may stay slow.

The global economy faces unquantifiable geopolitical risks.

But this doesn't necessarily give us a direction for India's corporate earnings.

Government policy will play a big part in influencing FPI attitudes.

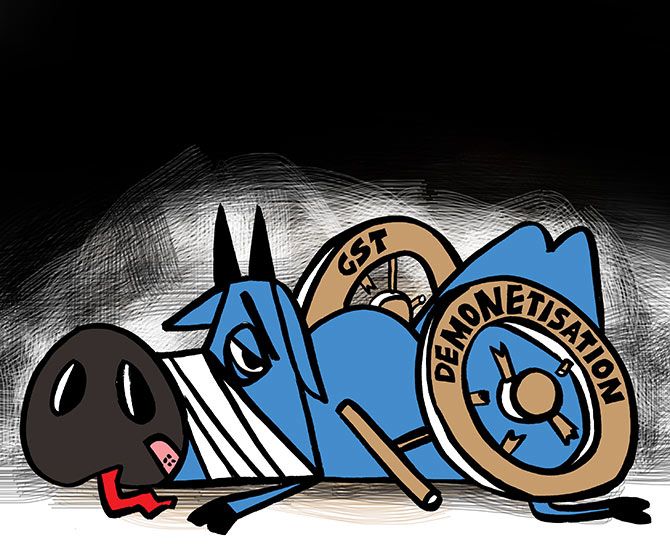

The last few years have been dismal, what with GST struggling, and demonetisation retarding growth.

The economy is very close to hitting crisis point and that could mean reforms triggered by desperation.

Real divestment -- as opposed to cross-holdings between government firms -- would be one possible way to signal seriousness about reform.

Another positive signal would be direct tax reforms, along with sincere measures being taken to improve ease of doing business.

In the absence of such signals, India's stock market may underperform other emerging markets.