India caved in to a bad deal at Copenhagen, says Praful Bidwai.

By sealing the so-called Copenhagen Accord with the United States, the BASIC grouping (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) has mocked at the multilateral negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), destroyed the unity of the developing-countries bloc, the Group of 77 + China, and paved the way for accelerated global climate change.

By sealing the so-called Copenhagen Accord with the United States, the BASIC grouping (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) has mocked at the multilateral negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), destroyed the unity of the developing-countries bloc, the Group of 77 + China, and paved the way for accelerated global climate change.

The BASIC countries had pledged to rescue the climate talks from the machinations of those developed countries which are bent on avoiding their climate-related obligations. Instead of using its clout to press them to do so, BASIC colluded with some of them.

The Copenhagen Accord is a shady, stealthily executed backroom deal between these five countries and was extended to only 26 of the 193 countries represented at Copenhagen. It was principally driven by the United States and China, with India's complicity.

Contrary to propaganda, the Accord isn't a 'win-win' deal, an honourable compromise, or a first step to a better deal. It runs against the imperative of an ambitious, effective, equitable and legally binding agreement, which the world desperately needs to fight climate change. It's deeply iniquitous because it will increase the disproportionate burden that climate change already imposes upon the world's poor people. It thus represents a disaster for the vast majority of Indians.

The Accord contains no short- or long-term targets for emissions reductions and no quantified obligations for individual countries -- unlike the 1997 Kyoto Protocol -- and no compliance or penal provisions. Countries are left free to do what they like. In other words, nothing.

Going by experience and the pressure which powerful corporate lobbies exercise on the developed Northern governments, they are highly unlikely to undertake serious voluntary obligations. The Kyoto Protocol imposed a modest average reduction of 5.2 per cent from their 1990 emissions by 2012.

Yet, only a minority of Northern countries is on track to meet their targets. Some will nominally achieve theirs by using the cheap and easy route of buying carbon credits from the developing South. The world's greatest historical polluter, the US, didn't even sign the Kyoto Protocol and has increased its emissions by 14 per cent since 1990.

Only a strong, comprehensive and legally binding agreement would have ensured that the North cuts its emissions (over 1990) by 40 per cent by 2020 and by 90 per cent by 2050, and that global emissions peak by 2020 and fall by 50 per cent by 2050.

Climate science is unanimous that such cuts are necessary if there's to be a 50-per cent chance of limiting global warming to 2° Celsius over pre-industrial levels, beyond which the Earth could reach a tipping point and hurtle towards catastrophe.

Under a new, equitable climate regime, the North would also have to support the South's voluntary efforts at limiting its emissions and at adaptation to climate change -- both financially and technologically. The bigger fast-growing Southern economies -- particularly, the Plus Five comprising China, India, Brazil, Mexico and South Africa -- would have to achieve reductions from business-as-usual scenarios so that the whole world moves towards climate stabilisation and sustainable low-carbon development.

Northern countries averse to such a deal revealed their hand at the pre-Copenhagen talks at Bangkok (September-October) where they mounted a frontal attack upon the Kyoto Protocol and the Bali Action Plan of 2007. They assailed the very principle of differentiation of responsibility between North and South. Australia proposed a draft which abolishes that principle and advocates voluntary legally non-binding "schedules" for each country for climate-related actions.

The G-77+China strongly deplored this and declared that a Northern failure at Copenhagen to agree to post-2012 commitments under Kyoto would be seen as a collapse of the talks and a betrayal of the trust the world has placed in the North's leadership. That has now come about.

The Copenhagen Accord was reached by circumventing the multilateral UN process and has no legal status. It's even worse than the Australian draft minus the 'schedules'. Its main merit is that it 'recognises' the scientific view that global temperatures should not rise above 2° C and promises some financial support and assistance to the South. But there's no commitment to the 2° C goal. In fact, according to a Massachusetts Institute of Technology team, temperatures will rise to 3.9° C thanks to the Accord and the North's paltry emissions-cuts offers of 14-18 per cent. This will accelerate dangerous climate change.

The cruel irony about climate change is its double iniquity. Its principal cause lies in the North, but its real victims are in the South, which is more vulnerable to rising sea levels, floods, droughts and rainfall changes that affect agriculture. That's why Sudan's Lumumba Di-Aping, a spokesman for the G-77+China, dramatically compared the Accord to sending "6 million people into furnaces" and to asking Africa to "sign a suicide pact, an incineration pact, in order to maintain the economic dominance of a few countries".

Even on funding, the Accord only promises $10 billion in annual aid to poor countries for three years, and sets the eventual goal at $100 billion a year by 2020. These are minuscule amounts. For instance, adaptation -- adjusting to or coping with cyclones, floods and droughts by building shelters, creating early warning systems and evacuation plans, and changing cropping cycles -- will alone cost upwards of $100 billion annually beginning now. By 2020, the South will need $300-400 billion in annual support. But the Accord assigns no quotas to any country.

The US struck the Accord on the cheap -- without raising its paltry offer of a 4-per cent emissions cut. President Barack Obama barged into the BASIC meeting. And China too played dirty by eliminating all relevant numbers from the text.

The BASIC countries capitulated because that would entail lighter climate-related commitments for themselves. This was perhaps sweetened by monetary rewards. BASIC brazenly deserted the G-77.

The ground for this was prepared earlier, as Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh's leaked letter of October 13 showed. Mr Ramesh proposed that India consider its identity as a member of elite groupings (G-20 and the Major Economies Forum) more important than its G-77 membership.

He also proposed more transparency in reporting India's domestic actions to the UNFCCC every two years, like the North does, but pledged that they wouldn't be subjected to international monitoring. This was one of his three Red Lines, the other two being no binding emissions-reduction obligations, and an emissions-peaking year for India.

The Copenhagen Accord crosses the verification Red Line too. Under it, India will report its domestic actions for 'international consultation and analysis'. This could open a Pandora's Box through intrusive verification. The US has already interpreted 'consultation' to mean 'review' and even 'challenge'.

Verification would be acceptable if the South's actions are supported by Northern funding. But it makes no sense to allow verification of unsupported actions. Mr Ramesh admits he executed a shift, but wrongly rationalises it as 'flexibility'.

However, India's retreat on this pales into insignificance beside the Accord's harmful implications for the entire world. India has become complicit in an ineffective and bad deal without quantifiable targets for the peaking and reduction of emissions globally or for groups of countries. This may be in the short-term interest of the Indian elite. But it's a disaster for the masses.

As I argue in my just-released book An India That Can Say Yes: A Climate-Responsible Development Agenda for Copenhagen and Beyond, there is a powerful strand among Indian policy-makers which has long rooted for an ineffective and weak deal because that would allow India to raise its emissions -- regardless of the consequences for the world's, and in particular, India's poor, who will suffer from increased hunger, water shortages, floods, displacement and disease caused by accelerated climate change.

This strand has always preferred a bad and toothless deal to a good, equitable and effective agreement -- so that India gets away with lighter obligations even if the North is let off the emissions-reductions hook altogether. This means cutting one's nose to spite one's face.

This suicidal course will lock the world into a high-emissions trajectory for yearswith terrible consequences. India can't pretend that it was forced into this Accord. It willingly went into it, and colluded with China in excising even the North's emissions-reductions offers from the text.

It's pointless to blame Mr Ramesh for this Himalayan blunder. Dr Manmohan Singh was personally responsible for India's policy disarray and eventual U-turn: from an emphasis on a strong, legally binding deal, to a dishonourable and disgraceful outcome.

This speaks to a larger foreign policy failure. India has let down its own allies. India is a rising power. But it doesn't know how to use its growing clout in the global, regional or national interest and, above all, the interests of its own poor.

As we gather the pieces from Copenhagen, there is a small window of opportunity in the next few weeks to rescue the UNFCCC process from further disaster by making a strong thrust for an equitable and effective global deal. This means returning to urgent collective action and fair burden-sharing with enforceable targets and measurable outcomes.

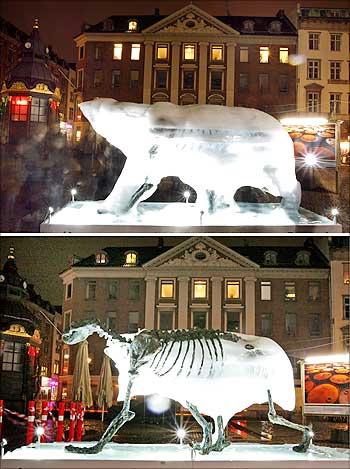

Image: A combination photograph shows an ice sculpture of a polar bear as it melts to reveal a bronze skeleton in Copenhagen. The first picture (top) was taken on the day the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen began. The installation was a part of an initiative to put focus on the consequences of global warming. Photograph: Pawel Kopczynski/Christian