Many stalled projects are about to get going again, providing potential relief to banks, says T N Ninan.

The last few months have been full of bad news about banks and their bad loans. The sums involved in quarterly loan write-offs, provisioning, restructuring and re-classification have climbed sharply, and bank stocks have taken a heavy beating on the market.

Many banks have been quoting at half their book value, implying a loss of confidence in bank accounting and performance. Given the poor reflection that this casts on bank managements, it is a brave man who will suggest that the worst of the bad news may be over - not because the banks have been transformed but because of market forces and government action.

Take three of the major troubled sectors which account for good chunks of the ‘stressed’ assets of banks: steel, power and highway construction. In steel, the government has taken one step after another to crack down on imported competition, raise domestic prices and engineer a situation where steel imports have pretty much stopped.

The action began last summer with the stepped imposition of import duties. Then there was the announcement of quality controls on imports, followed by the slapping on of a 20 per cent safeguards duty and finally the announcement of such generous minimum import prices as to suggest intense lobbying and more by the steel industry (leading, as a downstream consequence of such heavy-handed protectionism, to higher car prices).

Domestic steel prices have climbed sharply, and steel manufacturers confirm, privately and in one case publicly, that the losses that they reported through last year are a thing of the past. What this means for the banks is that loans of well over a trillion (lakh crore) rupees that were in trouble (though in some cases not formally recognised as such), could now come good.

In the case of power, it’s been the opposite situation: lower import prices for fuel have provided the solution, not caused a problem. Global gas prices have crashed from a peak of over $20 per mmbtu (million British thermal units) to less than $2.

Despite the heavy costs of liquefaction, transport in specialised ships and re-gasification of imported gas, the landed cost of liquefied natural gas (LNG) works out to about $5.50 per mmbtu. This is comparable for the first time to the government-determined price of domestic gas ($5.60), and is notably cheaper than the $8.40 that the Rangarajan Committee had recommended for domestic gas a couple of years ago.

This should be a boon for gas-based power stations, which have a combined capacity of 25,000 MW. These were running at barely 20 per cent of capacity over the past year, and even less before that; a government subsidy for imported gas made only a marginal difference.

But the subsidy is no longer required, and the logical culmination should be that gas-based power stations connected by pipeline to LNG terminals can operate at much fuller capacities - with the downstream benefit of bank loans being serviced.

Power supply will improve too, of course, for the additional reason also that the ‘Uday’ package for clearing accumulated discom debt will pave the way for demand to grow.

Finally, there is the progress made in re-starting hundreds of stalled highway projects, involving investment of tens of thousands of crores of rupees. The transport minister has been putting out numbers on what percentage of stalled projects have been re-started, but since he is given to exaggerated claims it is difficult to assess with precision how much progress has actually been made.

Nevertheless, anecdotal accounts suggest that many stalled projects are indeed about to get going again - once again providing potential relief to banks (and also a boost for the construction sector). All this is good news for the health of banks, for other important parts of the economy, and therefore for promoting economic activity across the board. The coming quarters will show to what extent this is so.

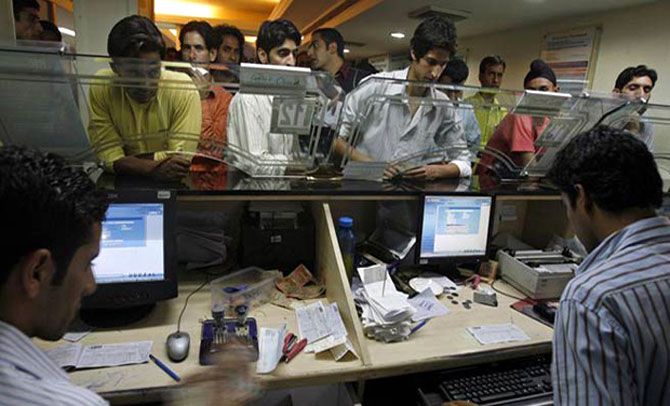

Photograph: PTI