A Singapore minister gets 60 per cent of the salary earned by the 500th highest paid person in that country’s private sector. It’s not 100 per cent because you are in public service, and expected to make a sacrifice. What if we applied that benchmark to India? The answer might surprise you, says TN Ninan.

How should one judge what the Pay Commission has recommended for government employees?

How should one judge what the Pay Commission has recommended for government employees?

Let’s start at the top, and use Singapore as a reference point because that city-state is known to pay its top people very well.

A Singapore minister gets 60 per cent of the salary earned by the 500th highest paid person in that country’s private sector.

It’s not 100 per cent because you are in public service, and expected to make a sacrifice. What if we applied that benchmark to India? The answer might surprise you.

This paper did a study last year of senior-level private sector salaries in listed companies, and found that 640 people earned more than Rs 1 crore.

So the 500th person would have earned a little more than Rs 1 crore.

Against that, the Pay Commission has recommended Rs 2.5 lakh per month (Rs 30 lakh per year) for the Cabinet secretary and equivalent positions.

Then count the perks -free housing, medical care, etc.

The people who get top-level salaries without the perks are the heads of the various regulatory bodies, like the telecom regulator.

They will now get Rs 54 lakh a year.

That can be taken to be less than the monetary and non-monetary value of what will go to the Cabinet secretary, who also gets post-retirement perks like lifelong pension indexed for inflation and lifelong medical care.

Thus the apex civil servant’s effective cost to the government would certainly be more than Rs 60 lakh per annum.

In other words, at the senior-most levels, the pay being offered now should not be a disincentive for public-spirited people with ability, provided income maximisation is not their goal.

At the bottom of the ladder, the Pay Commission’s recommended minimum pay of Rs 18,000 is of course way above market, being about twice the official minimum wage.

Some 85 per cent of government employees are in the C and D categories — drivers, peons, clerical staff, assistants, et al.

Add the value of their perks, and it is clear that the overwhelming majority of government employees will be paid much more than they should.

The government has no choice other than to accept this; Pay Commission awards are always honoured, often improved on. What the government can do is change the way it works, to reduce the need for support staff.

What if you move away from absolute levels of pay, and look at the level of pay hikes recommended after a decade?

The increase in the minimum and maximum wages, from the last Pay Commission to this one, works out to an annual increase of about 11 per cent — which is not out of line when nominal per capita GDP growth (i.e. the real GDP growth plus inflation) has been more than that.

It isn’t clear what the increase would be if you include allowances, especially since housing allowance has gone up steeply. What is clear is that the total bill is already 3.1 per cent of the GDP, and will go up next year — perhaps to 3.5 per cent of the GDP.

That’s high by the standards of the past.

Which brings up the question of affordability.

Every second rupee that the central government collects and keeps as tax revenue goes for pay and pensions.

That’s this year; next year it will be more.

If you look at the Centre’s tax and non-tax revenue combined, leaving out only money that is borrowed, every third rupee of such revenue goes to pay and pensions.

If you look at the expenditure side, every fourth rupee that the government spends goes to pay and pensions. Another rupee goes as interest on accumulated debt.

All the other items on which the government spends, and on which finance ministers make those long speeches on Budget day, get only half of the total expenditure; mostly, you don’t hear much about the other half, and it is time to ask why.

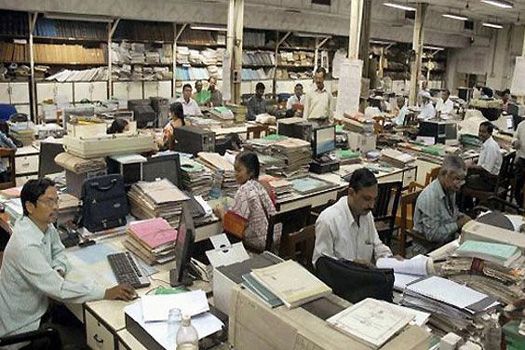

Photograph: PTI