Investor enthusiasm for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s policies is starting to wane, and only big-ticket reforms in the Budget can give it a boost, notes Andy Mukherjee

The upcoming Union Budget will be a test of just how many big ideas Prime Minister Narendra Modi can squeeze into a narrow fiscal space.

The upcoming Union Budget will be a test of just how many big ideas Prime Minister Narendra Modi can squeeze into a narrow fiscal space.

Curbing the federal deficit is the government’s absolute priority on February 28.

New Delhi is desperate to revive private investment, and the Reserve Bank of India has made it plain that it will only cut interest rates if belt-tightening continues.

The medium-term target is to reduce the shortfall to three per cent of gross domestic product in two years, from an estimated 4.1 per cent.

That means the government must tighten its belt by at least half a percentage point of gross domestic product over the next 12 months.

But a squeeze on public spending won’t be enough. The Budget also needs to strike a radically pro-business note.

Big-ticket reforms, which can lift sagging corporate profitability and revive animal spirits, will be crucial to boosting the credibility of the government’s policies.

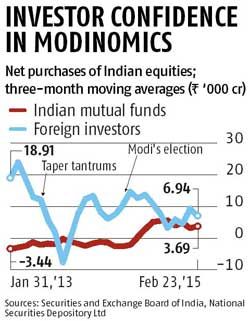

Investors’ confidence in 'Modinomics', while still high, is starting to wane (see chart).

Earnings at India’s top 100 companies by market value suffered an unexpected six per cent decline in the last quarter -- a big setback. Recently revised official statistics claim that GDP growth has accelerated to 7.4 per cent, from just 5.1 per cent two years ago.

But lacklustre corporate earnings, weak tax collections and subdued credit demand suggest otherwise.

Budget 2015: Complete Coverage

It’s true that companies are announcing many more new projects than before.

But for this to turn into a self-sustaining cycle of higher investment, more employment and greater consumer spending, Mr Modi needs to step on the gas.

Here are the five most urgent reform priorities, ranked according to the likelihood of their adoption.

Goods and services tax: almost certain

Goods and services tax: almost certain

The legislation to introduce a nationwide levy, which will replace a plethora of sub-national taxes, is already in Parliament.

The much-delayed measure is expected to come into effect from April 2016. This reform would go a long way toward unifying the small, fragmented markets of 29 Indian states. Both manufacturers and consumers would benefit enormously.

Inflation targeting: very likely

Another important change may be a revamp of the central bank’s monetary policy framework.

India was caught out in the summer of 2013 when double-digit inflation and a sliding rupee made foreign investors wary of financing the country’s large current account deficit.

That experience has convinced the authorities of the need to stabilise expectations of future price increases.

Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan wants a formal inflation-targeting mechanism.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley might just give him the go-ahead.

Well-anchored inflation expectations would obviate the need for sharp increases in interest rates. In the long run, growth would get a boost.

Investment sops: likely

The government wants investment and jobs.

It also wants its flagship 'Make in India' campaign to succeed.

But it doesn’t have the capacity to offer too many tax breaks.

Even so, the Budget will probably select a few areas where it expects big gains -- railways and manufacturing of defence goods are the most obvious candidates -- and give some incentives to investors.

The consumer electronics industry could be another beneficiary.

With labour costs in China on the rise, India can pitch itself as the world’s factory for assembling everything from washing machines to mobile phones.

Per-capita income is now high enough to generate domestic demand for these products.

Export-oriented supply chains can also take root, provided manufacturers can bring in parts duty-free.

Last year’s closing of a Nokia mobile-phone factory near Chennai over a tax dispute should serve as a wake-up call.

The Budget offers the finance minister the perfect opportunity to make amends.

Subsidy cuts: likely

Investors would also like to see more evidence of a decisive end to the previous government’s expansion of India’s welfare state.

Mr Modi has been lucky so far: thanks to a collapse in global crude oil prices, consumer subsidies on fuel are likely to be significantly lower.

But that still leaves food and fertiliser.

Reducing subsidies to farmers has proved politically knotty before and won’t be any easier this time.

But decontrolling the price of urea, and paying farmers a liberal cash allowance linked to how quickly they reduce their dependence on this overused fertiliser, would be a welcome innovation.

Privatisation: not very likely

Mr Modi has so far shown little willingness to go further than the previous administration when it comes to selling state assets.

The government’s only success has been in holding a successful auction for coal blocks, although power producers seem to have overpaid for the mines.

The bigger worry is the reluctance to sell controlling stakes even in very badly run companies like Air India.

Offloading some shares in better-managed public sector companies is just a fiscal expedient.

Without any change in management, the economy doesn’t benefit from enhanced productivity of labour or capital.

Such productivity gains are most urgently needed in the financial system.

Finance Minister Jaitley could transfer the government’s majority stakes in state-controlled banks to a newly created investment holding company. This is what an advisory panel set up by the RBI suggested last year. Creating a sovereign vehicle to manage state assets would be a sensible first step to eventual privatisation.

Further separating the management of state-run lenders from politicians and bureaucrats could allow for more commercial logic in lending decisions.

The culture of leaving taxpayers permanently on the hook for the losses of these banks would hopefully end.

Investors’ wish list from the Budget is long. Then again, there are reforms such as universal healthcare and old-age pension that investors won’t like.

But these will nonetheless become necessary after the government has acquired the fiscal muscle to shoulder the burden.

That day doesn’t need to be in the distant future.

Indian workers and entrepreneurs are young.

They can share bigger gains with the state -- provided Mr Modi can first deliver on his promise of showing them a good time.

Andy Mukherjee is the Asia economics columnist at Reuters Breakingviews in Singapore. These views are his own