'In the final analysis, all Budgets everywhere are like the schemes hatched by A A Milne's lovable Winnie-the-Pooh.'

'They may be well-intended, but often go awry.'

'Although Pooh and his friends agree that he 'has very little brain', he is occasionally acknowledged to have a clever idea, usually driven by common sense.'

'This Budget at a first glance does not appear to belong to that latter category,' says economist Shreekant Sambrani.

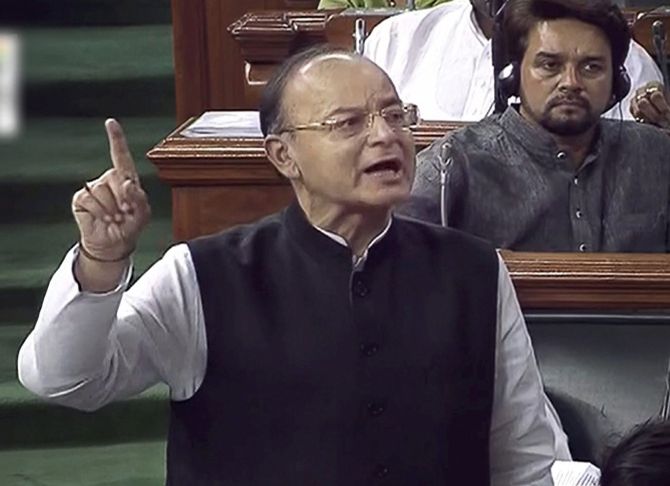

IMAGE: Finance Minister Arun Jaitley makes a point during the presentation of the Budget 2018-2019.

What distinguishes a rational human being from other animals (including some humans)?

I am alluding here to the much-maligned Homo economicus, not the flavour of the day in the Age of Behaviouralism. The singular trait of this creature is to plan the use of available resources towards maximising the gain of a desired objective.

This is based on a knowledge of means and ends, as well as an analysis of the proposed plan on the basis of past experience of achievements. John Stuart Mill summarised this behaviour in his Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy as (emphasis added):

'(Political economy) does not treat the whole of man's nature as modified by the social state, nor of the whole conduct of man in society. It is concerned with him solely as a being who desires to possess wealth, and who is capable of judging the comparative efficacy of means for obtaining that end.'

For example, before one decides to dine out, one is expected to review the past experience of various eateries, the fares they offered along with their tariffs and the satisfaction derived.

An impulsive decision without such analysis could well be trendy but a possible candidate for an exercise in mindless pursuit of pleasure.

Government budgets, as I had said in this space a year ago, are annual financial statements required to be prepared as a Constitutional obligation. Surely, they would be expected to incorporate the comparative efficiency judgment Mills referred to.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley presented the Budget for 2018-19 on February 1, in almost as laboured a manner and for as long a time as he did the last one a year ago. It was anticipated much more keenly than the earlier ones, because of two major reasons.

First, it would be the last full-year Budget of the present government before the general election next year.

Second, the talking heads of the media, electronic as well as print, had rather glibly interpreted the unexpectedly narrow win of the Bharatiya Janata Party in the Gujarat assembly elections in December 2017 as an indication of the rural voters' disenchantment with the party that had ruled the state for 22 years. (A more nuanced analysis would show that while there was a germ of truth in it, this was not entirely valid for all of Gujarat).

The Budget was thus expected to focus squarely on rural distress and propose measures to mitigate. The Budget was also expected to address the issue of employment generation.

The Budget certainly tried to do that, and much else, but unfortunately, showed little evidence of serious application of mind. That would need some elaboration.

***

IMAGE: Farmers spill milk on the road during protests in Nashik, Maharashtra, June 2017. Photograph: PTI Photo

Let us begin with the concern for rural India, the leitmotif of the Budget. All told, it was to receive an outlay of over Rs 14 trillion, according to the prime minister (including housing, infrastructure and all other related activities).

A logical starting point would have been to review what happened in the last year, when agriculture and rural infrastructure were among the ten thrust areas. The agricultural economy was expected to grow at 4 per cent.

Mr Nitin Gadkari, who had earlier headed the rural development ministry, went so far as to say that these measures would lead to annual agricultural growth of 6-plus per cent from the next year onwards.

That has clearly not happened. We did not hear what went wrong and how we would avoid a similar fate this year.

Perhaps that was inconvenient and embarrassing. But what about the emphatic assertion of payment of remunerative minimum support prices (MSP)?

After the familiar homily to the toiling peasantry, the finance minister assured the payment of MSP that was at least 50 per cent higher than the cost of production for all scheduled kharif and rabi crops beginning this very season.

MSPs have been around for over four decades. The cost-plus-50 per cent formula was first advocated by the National Commission on Farmers (2004-2014) under Dr M S Swaminathan. Yet it is amply documented that farmers have not always received such prices.

In the last year, they have often been paid market prices well below MSP. That led to farmer anger and violence in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan (both BJP-ruled, going to polls later this year) and a prolonged agitation in Tamil Nadu.

How does the government plan to overcome this situation? Mr Jaitley said the NITI Aayog will propose a way.

Why has this not happened so far? No answer.

The news on irrigation was similarly not very cheering. We heard allocations, but not what has been happening to those made in the last two years.

Nor did we find a mention of the rather eloquent analysis of global climate change and its impact on Indian agriculture contained in this year's Economic Survey (more on the Survey later on).

The cursory mention of linking over 22,000 rural markets to electronic national agriculture markets did not provide any review of this scheme over the two years of its existence. No prizes offered for guessing the reason, which is that there is little to show for it.

The biggest example of a lack of analysis is the proposed new Operation Green, which will replicate for vegetables what Operation Flood has done for dairying. The government has bought a bill of goods sold by a well-known economist, for long a part of the government support system.

Both milk and vegetable production suffer from seasonal factors, but face a steady demand. The consequent spikes in prices hurt both the producer and the consumer.

In case of dairying, processing provided the key. The flush season surplus could be processed into milk components, stored and recombined to form liquid milk to augment lean season supplies.

The producer and the consumer would enjoy stable prices year round. Operation Flood did this through co-operatives, but elsewhere in India and the world, private enterprise has also done the same.

The crux is processing, not the organisation.

Processed milk constituents can be recombined into liquid milk, but dehydrated onion cannot become a fresh onion, nor tomato paste be made into a fresh tomato. So the milk commodity experience of evening out prices cannot be replicated for vegetables, a fundamental point that has escaped the learned economist-champion of the scheme, and now, alas, even the Government of India.

On the same subject, the Budget once again sang praises of food processing. The fact remains that ever since the government began to recognise the role of the industry and even formed a ministry for it as far back as 1987, its performance in either boosting farm incomes or consumer satisfaction has been marginal at best.

Yet year after year, we keep playing the same song.

Agriculture exports, the minster claimed, have a potential of $100 billion a year, but we have only reached $30 billion. He did not elaborate why, because that would have raised uncomfortable (for this government) questions about buffalo meat exports.

It would also have led to issues such as whether we could afford to use up 5,000 tons of scarce water required for every ton of rice exported.

***

IMAGE: A scene from a rural school in India.

'Students poor in all their learning and abilities are emerging from the system. And this is not getting any better,' points out Dr Sambrani.

And rural India is not the only area where activities are proposed without application of mind.

Take for example, the next in priority, education.

Suppose your child is persistently falling behind in school performance despite having tutors. Would you continue to engage more tutors, who might on paper possess better qualifications, without going into reasons why this is happening?

The answer to this rhetorical question is obvious, but not to the government.

Our abysmal state of primary education is now well-documented by the Annual Status of Education Reports and the government's own large National Achievements Survey. Students poor in all their learning and abilities are emerging from the system. And this is not getting any better.

The government response: More of the same, with more teacher training programmes, and so on.

The same applies to the national skilling programmes.

The fact today, again well-documented, is that most of the artisans from Industrial Training Institutes or the so-called engineers from the mushrooming engineering colleges possess little employable skills of any worth.

We still keep talking of the demographic dividend, little realising that it could turn into a ticking time-bomb.

And we continue to genuflect at the altar of the programmes with titles which are either alphabet soups or grandiloquently evocative of the past.

The Ganga clean-up will receive 187 new projects. What has happened since the programme was launched more than three years ago or the minister in charge was replaced six months ago?

I am no expert, but all reports say that the river is now more polluted than ever before.

Railways will get a capital expenditure of Rs 1.5 trillion, but will that be directed at least in part at making travel safer?

Thousands of stations will get escalators, but how does having a set of them only on one platform of the several at a large station increase passenger comfort? They must still negotiate the awkwardly constructed and crowded staircases at the other end.

We modernise airports with aerobridges to connect the aircraft to the departure area, but why do we still have many of them not being used, even in Delhi and Mumbai?

The Budget proposals have many more such ideas which need a through scrutiny, but space does not permit citing more of them.

***

IMAGE: A new born baby with relatives at a primary health centre in north Bihar. Photograph: Archana Masih/Rediff.com

'Will the largest health scheme anywhere in the world deliver results for those in need is a moot point?' asks Dr Sambrani.

This Budget had two big bang items, the consequences of which will not be immediately evident.

The first is the imposition of the long-term capital gains tax which aroused the ire of Dalal Street instantaneously.

The stock market, which had been experiencing a sugar rush in Lawrence Summers' memorable words, dipped sharply after hearing the much feared announcement, but then slowly recovered, to end the day relatively unchanged.

How will the investor community, international and domestic, react over time is not clear, but surely this will be a matter of some considerable pressure for the government.

The other was the health insurance coverage up to Rs 500,000 a year for 500 million Indians (100 million families) at government expense, touted as the largest such scheme anywhere in the world.

But whether it delivers the results for those in need is a moot point. The report card of a similar universal crop insurance scheme has not been very encouraging so far.

One has noticed that for the last two years, the pre-Budget Economic Survey has numerous elegantly written and crafted analyses. Last year's Survey had a long disquisition on Universal Basic Income and footwear and clothing as export candidates.

The current Survey has talked about global climate and its consequences for India's agriculture, gender issues including meta preferences for sons and unwanted daughters, among others.

Why do these not find a place in the Budget? And if they are not to be used, why does the Economic Survey contain them, except for unrequited academic satisfaction?

In the final analysis, all Budgets everywhere are like the schemes hatched by A A Milne's lovable Winnie-the-Pooh. They may be well-intended, but often go awry.

Although Pooh and his friends agree that he 'has very little brain', he is occasionally acknowledged to have a clever idea, usually driven by common sense.

This Budget at a first glance does not appear to belong to that latter category.