'As long as the government owns the banks, bankers will follow signals from politicians as to how to lend.'

'State-owned banks will remain State-owned banks as long as the current dispensation is in power -- and certainly there will be no change if the other chaps get in,' says Mihir S Sharma.

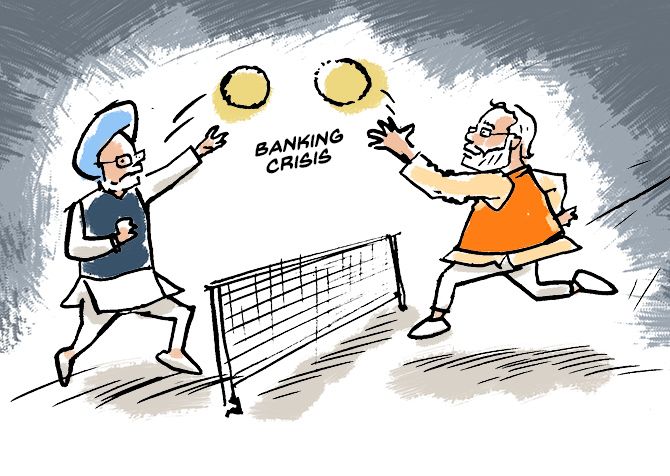

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

You'd think that economists would be happy that, for once, everyone is talking about factor markets. Well, more precisely, they are talking about the conditions attached to capital availability in India -- who gets bank loans and why.

After all, economists have complained for decades that factor markets in India -- land, labour and capital -- are so antiquated and restrictive that they have held back economic growth and poverty reduction.

Yet the controversy about non-performing assets and bad loans -- a controversy that looks close to being upgraded to a scandal -- has been overtaken by political rhetoric and scapegoating, instead of producing a genuine effort to work out what happened, what went wrong, and how to fix it.

Yes, it is true that there are genuine questions to be asked about the cronyism attached to certain specific bank loans. And about whether there is accountability for politically connected defaulters.

The burning question of the moment: How exactly did Vijay Mallya manage to leave the country in spite of the fact that he had had a 'lookout notice' against him at Indian airports?

The Central Bureau of Investigation diluted the requirements in the notice, and it now claims that it imagined Mallya -- known for having several houses worldwide -- was not a flight risk.

This, of course, is literally incredible; many questions need to be answered about whether there was any political influence on that decision.

The accusation, which the Union finance minister has partly confirmed and partly denied, that Mallya spoke to him about a possible deal, has added to the politically explosive nature of this entire sequence of events.

Then there is the Nirav Modi question; and the Mehul Choksi question; and so on.

Yet Mallya's argument that he is being scapegoated for a much larger problem, while not exculpatory, nevertheless should not be dismissed out of hand.

It's hard to claim that he was the worst such offender. Raghuram Rajan's note to parliamentarians who had enquired about the NPA problem also contained an aside about a letter that he had written to the prime minister's office.

It was a request for an inter-agency investigation of the holders of suspect accounts that had also run up large NPAs and exhibited other suspicious behaviour.

In a well-ordered country with an active and unfettered media -- such as India was till quite recently -- the inaction on this letter would have required a direct answer, maybe in a press conference, from the prime minister himself.

Is Rajan's statement genuinely of concern? Consider what we do know. It is a matter of public record that there are several such accounts.

Rajan's claim that there were several promoters who habitually over-invoiced exports -- in other words, got money out of the country illegally -- is also no doubt valid.

The question of why these companies were not investigated, and why in fact some of them have continued to be beneficiaries of government patronage, is one that certainly should be answered.

Rajan was governor of the Reserve Bank of India; he had no power over, say, the enforcement directorate.

The question is, why those who did have power over the ED effectively ignored a serious warning from the central bank governor. They were under no compulsion to follow Rajan's advice, certainly -- but voters need to be told why they chose to completely overlook it.

Certainly, in the absence of any such explanation the government's repeated insistence that high-level corruption and cronyism has ended sounds weak and unbelievable.

The current administration's insistence that the NPA problem was created and sustained entirely by the previous regime also needs to be questioned.

There is little or no doubt, of course, that bank credit in the past was provided and extended to those who were politically connected.

But this has been, by all accounts, an endemic problem in the Indian banking sector.

What is exasperating for many of us is that the political back-and-forth has completely failed to make this point.

The NDA government claims that 'phone calls' from Delhi to banks have stopped. Phone calls? How very 2008.

We are supposed to believe, therefore, that bankers have no other way of being communicated political preferences.

As long as the government owns the banks, bankers will follow signals from politicians as to how to lend.

Yet State-owned banks will remain State-owned banks as long as the current dispensation is in power -- and certainly there will be no change if the other chaps get in.

Even when faced with a banking crisis, the government has not even attempted to address the root cause of decades of bad loans.

And that is why, I suppose, economists will not be completely happy about NPAs' sudden political salience -- politicians seem to be extremely courageous about accusing each other of corruption, and incredibly cowardly about addressing the structural features of the economy that enable corruption.