Luckily for him, Modi once again has a golden opportunity to go down as a great reformer. He has four and a half years of opportunity. Let’s see how he uses them, says TCA Srinivasa Raghavan.

Nirmala Sitharaman has been the butt of much harsh criticism and crude jokes for about two months. These became quite brutal after the first quarter GDP numbers came out.

It was not her fault. The Budget she presented was more-or-less handed to her. Its mistakes were, in large part, because of the finance secretary and a joint secretary in the Prime Minister’s Office. Both have since been posted out. The former has resigned in protest.

For the last one month the finance ministry, faced with a severe resource shortage, has been coping as best as it can. It’s announced relaxations and handouts when it cannot afford them. The latest cuts in corporate tax are very brave in that context because it entails a loss to the exchequer of nearly Rs 1.5 trillion.

Taken along with the likely shortfalls in indirect tax revenue, it’s clear the stupid adherence to the 3 per cent fiscal deficit target is now history. Thank god.

What next?

So what, apart from some ineffective cash injection and much need tax reform as is being attempted now, should the government do? How can the economy clamber back more quickly? The answer lies, squarely, in five things.

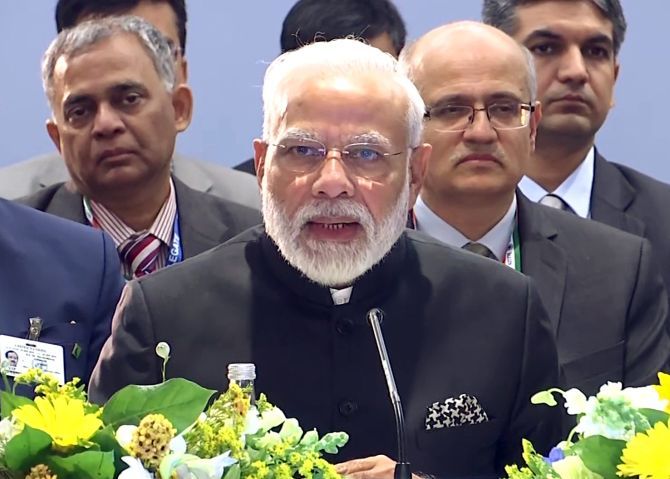

First, Prime Minister Narendra Modi must admit he was wrong and instruct the finance ministry to move 90 per cent of the things from the zero rate, which makes no sense at all, to the 5 per cent category. Simultaneously, all rates above 5 per cent should be combined into a single 18 per cent.

Second, personal income tax rates must be reduced to two slabs of 20 and 30 per cent in the next Budget and the tax threshold increased to Rs 18 lakh. That is, if a person earns Rs 1.5 lakh or less a month, he or she should pay zero tax.

This might seem like a lot but given the structure of inelastic costs that a typical middle class income earner faces, it really isn’t. I had written about this some weeks ago. It’s to do with very high services inflation which all governments have ignored so far and the changed family sociology in urban settings.

Third, there’s asset disposal. The only assets that can be sold off without trade union and safety net issues is land. The government must initiate this process at once for funding its social programmes. No one will complain then.

Fourth, there is the question of funding temporary revenue shortfalls. I have been writing for the last one year that the time has come to revive ad hoc treasury bills in a modified form. They are the equivalent of printing notes and are a recourse of last resort.

The point is this: Just because Rajiv Gandhi made them a staple from 1986 to 1989, and consequently landed us in a mess in 1990, doesn’t mean they were altogether bad. The fact is they served an important need.

What needs to be done now is to raise the current cap on them which, at Rs 100,000 crore, is too low. It was set in 20 years ago.

Fifth, very crucially, the notion that expenditure is what governments want it to be and revenue must be raised to meet it must be discarded. Tax and spend is not the same as spend and tax.

Hence, contrary to the popular demand that the government must spend more, a massive expenditure compression is what is needed and, personally, I think only Mr Modi has the stature and chutzpah to get it done. An across-the-board cut of 15 per cent for the next five years will do the trick. It’s been done before in 1967, 1974, 1981 and 1991.

The Bimal Jalan committee which was set up soon after Mr Modi came to power in 2014 had some very useful ideas. In essence what this entails is expenditure switching and eliminating payments to the undeserving like retired persons with incomes from non-pension sources.

A lucky PM

Modi started with a crisis in 2014 and again in 2019. The first time around, he blew it. He thought the reform of service delivery alone was enough. This was the opposite of Rao-Singh reform which assumed that macroeconomic reform alone was enough.

Luckily for him, Modi once again has a golden opportunity to go down as a great reformer. He has four and a half years of opportunity. Let’s see how he uses them.

About one big game-changing reform he can do -- we know he excels at these -- I will write next time.

Hold your breath till then.