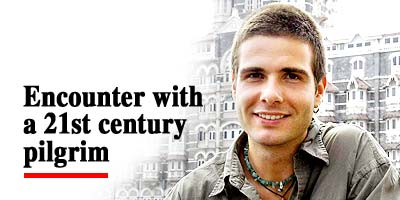

The 28 year-old German man sitting before me looks nothing like a sadhu. He's supposed to be one, according to the press release accompanying his first book, Return to La Paz. But he simply doesn't look the part. "I'm Thomas Reissmann," he says, smiling, fingers playing carelessly with a string of beads around his neck. He refuses my offer of tea or coffee, asks for water, and says he's ready to answer any questions that I might have.

And yes, I have questions. You would too, if you knew what I know about Mr Reissmann.

To begin with, there's that little detail about his growing up behind the Berlin Wall. When it collapsed, he decided to make up for lost time and see the world. He began with high school in California, followed it up with courses in tourism management in the UK and Australia, then opted for a research assistantship in Costa Rica. And still, he travelled. To Thailand, Cambodia, New Zealand, and India.

Along the way, Reissmann found himself in South America, indulged in Shamanism and a drug called ayahuasca, and was briefly involved in the region's deadly drug trade. Then, one morning, he decided to stop, catch his breath, and write about his extraordinary life. The result was Return to La Paz. A bizarre account, but a true one nonetheless.

Now, wouldn't you have questions?

Considering the value he sets on searching for a higher, personal truth, I find his choice of subject tourism management a little odd. "It fits in, actually," he says, "because there's always something spiritual about travel. It's always a pilgrimage of sorts."

Reissmann claims to carry all his worldly possessions in his backpack. He has no fixed home or income, and works whenever and wherever he can in order to support his next trip. I point out that Indians believe freedom comes from within. They need not travel to find it. He agrees, but only partly. "When I visit Third World countries, I find extreme poverty and a complete lack of the distractions that enable Westerners to escape. People here are compelled to look within themselves, simply because there is little potential for movement without."

Looking for less weightier matters, I ask if sadhus have girlfriends. Reissmann blushes. He does have one. She lives in the UK, does all kinds of things, and meets him whenever they both have time. "It's always as if we are meeting for the first time," he says. "It's always a new experience."

Leaving romance aside, I turn to something more practical, like his backpack. What's in it? "A lot of books, a laptop, video camera and mp3 player." I smile. Reissmann smiles too. He knows there's something incongruous about what he has just described, but thinks of himself as "a 21st century pilgrim".

We decide to talk about the book a little. An interesting chapter in Return to La Paz involves the hallucinogenic brew ayahuasca. Called yagé in Colombia, and ayahuasca in Ecuador and Peru, it is prepared from segments of a species of vine called Banisteriopsis. "It is boiled for around eight hours," says Reissmann, who admits to having spent at least one night under its influence. "When it cools, it's a thick, red-coloured concoction. A glass is enough to affect you for three to five hours. Some people have visions, others throw up."

Another book is already in place, in the manuscript stage. "It's called Generation Zen and is inspired by Robert M Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. The book is a philosophical discussion, but it's also a story of love."

I wonder about how long he can continue with this seemingly rootless existence. The only hint of semi-permanence comes from an interesting plan he has in the offing combining his professional tourism training with ecology and spiritualism to launch what he calls 'eco-spiritual tourism'. Yes, India definitely will be on the itinerary, he assures me.

I have one last question before he leaves. As a spiritual being moving in capitalist circles, is there something he would like to tell the movers and shakers of corporate India? "I would like to ask them if they are happy with the way they are living," he says, suddenly serious. "If they genuinely are, I have no problems with that. I also think the men in suits have the potential to make a difference."

With that, Reissmann is off, although he's not sure where to. "I don't make plans because they are pointless. They rarely work out, and they are boring." We part with a handshake. He turns towards the unfamiliar adventures of his world; I head for the staid familiarity of mine.

Headline Image: Uday Kuckian