Shanker Raman's Gurgaon is about a set of displaced people yearning for a home that no longer exists.

The film has its own music, a kind of Death Disco, and its characters live in a world of loud lighting and flickering lights, with decorations just this side of decay.

Each day a few more lies eat into the tissue with which these characters were born, and they continue to waste themselves.

This is the story of a city told through the story of a family it has spawned.

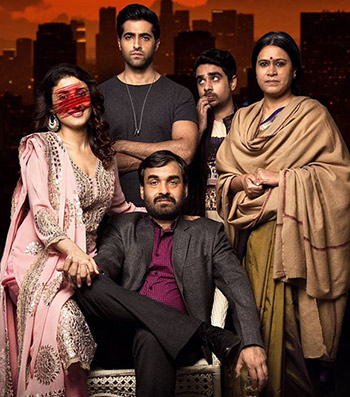

Since oozing into the millennium, Gurgaon has undergone a collective shift of identity, and despite Kehri Singh's (Pankaj Tripathy) attempts to place his signboards all over its changing landscape, the city today moves faster than him.

This zest for outwitting comes naturally to Gurgaon where the developed places are essentially little clearings in the forest; clearings that the forest tries to reclaim everyday.

Kehri Singh is a man of the forest; he once betrayed the forest for concrete, and the forest is now doing a number on him.

Singh's son (Nikki Singh, played by Akshay Oberoi) and his stooges drive away into the jungles to play their cruel games, and they live awkwardly in their glass-and-steel mansions but pee with great relief over the brick-walled homes in the city's outskirts.

Director Shanker Raman, with an appetite for noir and a natural temperament for fast-cutting, takes you so swiftly and so deeply inside Gurgaon's anomie that you may mistake his vision of the city for some dystopian view of the future.

Two people bloody each other up at a toll naka and drivers pass by the scene without even bothering to look (Contrast this with Mumbai where people wouldn't mind missing their Monday morning meetings just to play witness to a fight at a newspaper stand).

Gym memberships are pitched as 'your only chance of surviving a brawl.' (Powerhouse Gym: Where pacifists learn to give it back).

In a city of tall buildings, everyone's screaming to the heavens.

There's a rage about their flights as they scuffle with the other birds on their way up, their faces constantly dissolving into the moon or emerging from it.

Gurgaon deepens as it goes along, as Raman starts to cross-cut his narrative with reflections from the past.

It is at this point that the film becomes an epic version of the city's total corruption.

We see the origins of certain relationships and how their power dynamics got defined over time and we see the links between today's hunched shoulders and yesterday's sins.

The movie then asks some of the questions that Francis Ford Coppola tried asking in The Godfather II: What gets passed on in families aside from the genetic gifts? Is sin passed on? Is guilt passed on?

Kehri Singh is both scared for his son Nikki and scared of him -- for the simple reason that he happens to be his son.

When the movie begins, we see Kehri as an ageing patriarch, longing again for the sunshine world.

Pankaj Tripathy uses his eyebrows better than any other Indian actor and as Kehri Singh, Tripathy breaks his communications down into Brando-like mumblings and eyebrow-pointing, even as his face magically becomes a facsimile of all the battering he has taken and meted out.

Kehri taunts Nikki Singh -- as he should have taunted his younger self -- using Nikki's business idea-pamphlets like tissue paper and subjecting him to Broomstick Discipline when he steps out of line.

His real estate business has been assigned his daughter's name (Preet, played by Ragini Khanna). Preet is adopted and has been raised as Kehri's good-luck charm, and she's now taking Kehri closer to innocence.

Nikki has Kehri Singh's blood, but Preet has his conscience, and when they share a dinner table, she is served the pies and he gets the pickles.

Akshay Oberoi's vacant-eyed smile as Nikki suggests a childhood being lived over and over again; its twisted knots becoming more visible as the story moves on.

Oberoi gives his character eyes that are forever looking for the slightest sense of displeasure or contempt -- when he praises himself as he's driving, he checks in the mirror to see if his friends at the back are in agreement with him.

Once the self-appraising stops, the centrepiece of the movie takes over and it's concerned with Nikki getting Preet kidnapped: He wishes for both his father's money and his hurt.

Kehri, who lives a life of outward polish (Rotary Club chairmanship to go with the big malls he's erecting), is still blessed with instincts of the soil and he suspects Nikki of the act straightaway.

But this is a small city of big men, who wish to not get their hands dirty, even if they have hands best suited for it. So Kehri calls out to his brother Bhupi (Aamir Bashir) with whom he shares a relation soaked in blood.

Bhupi has none of the security that Kehri Singh craves for. He's a tough guy who doesn't dance. But he is also the most humanistic character in the film: Offering a security guard they have tied up his own jacket, and cradling a kidnapper-turned-victim in his arms, consoling him with the big-brotherly words: 'Mere hote koi na mare (Nobody dies till I am around).'

Bhupi asks Kehri to go along with the demand for ransom while he presides over its many rituals: Now, it's a cat-and-mouse game where the cat knows the little burrows and barns better than the mouse.

Shanker Raman isn't interested in giving us a straight thriller and as the narrative surges ahead, he progressively dims out the gap between Kehri Singh's present and his past.

At one point, they almost swim into each other, when Kehri, Nikki and a development officer Kalra go hunting.

'Don't breathe and try to talk in gestures,' Kalra instructs Nikki, as if he knows what Nikki is up to.

Here, a flashback is sandwiched between two scenes set in the present, as we see how Kalra got to know Kehri Singh, how they've drawn each other's growth graphs, and how Nikki sees them both.

That bit is a masterpiece of construction giving us both the arc of the land and the leads all in the space of 10 minutes, and it ends with the shooting of a shiny-eyed rabbit in the flash of a torchlight: a moment reminiscent of the hunting scene in Renoir's The Rules of the Game.

This Raman knows what tickles him and also knows how to pass on those tickles to us in the audience.

When the timelines aren't crossed, Shanker Raman plays with time within sequences: We're shown the epilogues first and the prologues later, the breaking of promise first and the phrasing of it later -- the movie then becomes almost Dostoevskian in texture.

Gurgaon touches upon topics such as misplaced masculinity and female infanticide, but it somehow deals with these topics better when they are buried inside the narrative and not worded using those exact terminologies.

When Preet speaks out the movie's subtext, we also get its weakest sections. It's like the last one-fifth of Huckleberry Finn where everything is verbalised, just so that we don't miss out on the 'messages'.

It's precisely at these points that the movie's editing also takes a hit, as the scenes get clipped away after they have told you what exactly to think -- like we didn't know where the good manna was.

Raman puts the soul of the film in a junkie guitarist/singer's mouth -- he is meant to be a stand-in for us the viewer, but the character has the effect of us wishing that we were kept totally out.

Visually, Gurgaon is stylised without it ever seeming synthetic; and when the movie projects artificiality it does so with a purpose.

There's a shot of Preet looking through her red-coloured blindfold, and Raman makes the screen go completely red there. It jolts you up, but there's also a logic to the style.

Raman and cinematographer Vivek Shah also map out carefully the positions that Kehri Singh and his wife (the brilliant Shalini Vatsa) occupy relative to each other, showing us in effect the changing dynamics between the two.

When they were peasants, she would watch him from a distance while cleaning the wheat, her ear attentive to his dark plans. Later, when he's a tired rich man, she's behind him directing him to the right room.

By the end -- as he unloads upon her a deadly secret -- they sit at two ends of a grand hall, with a clumsy portrait hanging between them.

Shalini Vatsa's wife is the most powerless character in the movie, but the film ends with her face after she has shut down an entire tradition -- and she does so by doing the thing most painful to her.

Shanker Raman knows that for Gurgaon to work, it must first establish a certain distance from the viewer. He gives us that distance so that we get both the heat of the orgy and its murder.

The film is supremely entertaining, and we may often find ourselves envying the vitality of its characters' lawlessness and also sharing their daze.

But just as we get caught up in all that, Raman suddenly pulls the rug out.

There is a moment in the movie when Preet's hired kidnapper comes to her office dressed as a pest control guy and looks at a plan she has laid out on her table.

The kidnapper talks about how their buildings rob people like him of their lands. Preet looks at him and she senses his loss, and we sense his loss, just before he puts the chloroform on her.

The city has in one instant opened its vein and shown you its tender side, and in the very next instant pulled you into its vortex and zapped you with its speed.