It is often remarked that few, if any, family-dominated and family-promoted business enterprises last beyond the second generation of entrepreneurs.

Typically, a pioneering individual establishes an industrial empire from scratch after displaying considerable effort and perseverance. He then bequeaths his assets to his children who squabble and go their own ways. By the time the third generation in the family arrives at the helm, the corporate group is a pale shadow of what it once was.

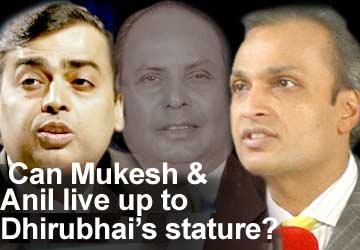

It would be completely foolhardy at this juncture to begin writing the obituary of the vast business conglomerate that was set up by the late Dhirajlal -- better known as Dhirubhai -- Hirachand Ambani from 1958 onwards after he returned from Aden where he had spent eight years having begun his career working as an attendant at an outlet for petroleum products.

The corporate empire that Dhirubhai Ambani left behind after his death on July 6, 2002, had a gross annual turnover in the region of Rs 75,000 crore (Rs 750 billion) or nearly $15 billion -- since his demise this figure would have risen by around a quarter.

Out in the open

Less than two years after the demise of one of India's best known -- and controversial -- entrepreneurs, not too many could have imagined that the tussle between his two sons, Mukesh (47) and Anil (45) would come out into the open.

A reporter from the CNBC-TV18 television channel had thrust a microphone at Mukesh Ambani when he was leaving the venue of a function in Mumbai where the main speaker was the visiting CEO of Microsoft, Steve Ballmer, and asked him where there was a likelihood of a split between the brothers.

While emphasising that the Reliance group separated ownership from management and that the group had 'moved beyond' a few individuals, Mukesh nevertheless acknowledged that there were certain 'ownership issues' that were in the 'private domain.'

While he did not elaborate on what these 'ownership issues' were that have presumably not been resolved in a 'very, very strong professional company,' the cat was out of the bag. For many months, speculation was rife in corporate circles that relations between the two Ambani brothers (and even their wives) were not exactly the most cordial.

However, such rumours were confined to gossip-mongers at cocktail parties. What was, however, evident to even the junior-most employees of Reliance group companies was that the two brothers had effectively carved out their personal domains of control and were, for all intents and purposes, working autonomously.

True, the two would show up on special occasions. But such bonhomie was evidently for public consumption.

Now that Mukesh's off-the-cuff remark has stirred a hornet's next, not too many will be surprised if the brothers come together again on a public platform and hug each other to scotch speculation to the effect that the industrial empire built so assiduously by their father was in some danger of coming apart.

Who controls what

For some time now, Mukesh has been focusing on the following businesses of the group: telecommunications, petroleum refining and marketing, petrochemicals, oil and gas exploration and life sciences.

Anil, on the other hand, oversees the electricity generation and financial sector activities of the group (including insurance, asset management and share transactions). He also heads the operations of the group that intend setting up what is being touted as the world's largest gas-based power project in Uttar Pradesh.

Unlike his elder brother, Anil is perceived to be close to Samajwadi Party leader Amar Singh and UP Chief Minister Mulayam Singh Yadav. It was rumoured that Mukesh did not approve of Anil's proximity to these politicians nor his decision to become a member of the Rajya Sabha.

Certain industries, notably the synthetic fibres and textiles part of the Reliance conglomerate, were reportedly being looked at by both brothers. In other sectors, there is an apparent overlap in the activities of the two areas overseen by the two brothers, notably the energy sector (that includes oil refining, gas exploration and power generation).

The cross-holdings of the major, widely held companies in the group are publicly known. For instance, the group flagship Reliance Industries holds a little over 41 per cent of the equity capital of Reliance Energy (formerly BSES or Bombay Suburban Electric Supply), while 45 per cent of Reliance Infocomm is held by Reliance Industries.

What is also known is the stake of the promoter group in a company like Reliance Industries -- members of the Ambani family and their close associates control nearly 47 per cent of the group's flagship concern.

However, what is not known to most is the exact manner in which the promoter group controls the large corporate entities in the group through complex holdings by hundreds of investment firms, closely-held companies and, perhaps, partnership firms, proprietary concerns, trusts and HUF (Hindu Undivided Family) entities.

Only insiders would know who controls which corporate body and how -- namely, knowledge about the 'family tree' of specific corporate bodies.

The problem

The problem is simple. Dhirubhai Ambani died intestate -- namely, he did not leave behind a will bequeathing his assets to specific members of his family, including his two married daughters, Deepti Salgaonkar and Nina Kothari.

What complicates matters is that under the regular laws of succession in the country the property of a person who dies intestate is divided between his widow and all his children; under the laws governing HUFs, daughters are not automatically eligible for a share in the property of a deceased father. According to the HUF laws, unmarried and widowed daughters can stake a claim to their late father's properties.

Meteoric rise

Dhirubhai Ambani had achieved what many would consider impossible. In a life spanning 69 years, he built from scratch India's largest privately controlled corporate empire.

He would often say that success was his biggest enemy. He was a man who aroused extreme responses in others. Either you loved him or you hated him. There was just no way you could have been indifferent to this amazing entrepreneur who thought big, acted tough, knew how to bend rules or have rules bent for him.

He was a visionary as well as a manipulator, a man who communicated with the rich and the poor with equal felicity, who was generous beyond the call of duty with those whom he liked and utterly ruthless with his rivals -- a man of many parts, of irreconcilable contrasts and paradoxes galore.

He died from a second cardiovascular stroke that hit him on the evening of June 24, 2002: the first had occurred more than sixteen years earlier, in February 1986, leaving the right side of his body partially paralysed. At his cremation, the well-heeled rubbed shoulders with the ordinary. No Indian businessman ever attracted the kind of crowd that Dhirubhai did on his last journey.

After his cremation on the evening of July 7 that year, Mukesh reminded a gathering of well-wishers that when Dhirubhai had arrived in Mumbai from Aden in Yemen in 1957, he had only Rs 500 in his pocket.

The second son of a poorly paid schoolteacher from Chorwad village in Gujarat, Dhirubhai Ambani had stopped studying after the tenth standard and decided to join his elder brother, Ramniklal, who was working in Aden at that time. Not surprisingly, the late entrepreneur ensured that his two sons went to premier educational institutions in the United States -- Mukesh was educated at Stanford University and Anil at the Wharton School of Business.

Having worked as an attendant in a gas station, half a century later, he would become chairman of a company that owned the largest oil refinery in India and the fifth largest refinery in the world, that is, Reliance Petroleum Limited which owns the refinery at Jamnagar that has an annual capacity to refine up to 27 million tonnes of crude oil.

In 1976-1977, the Reliance group had an annual turnover of Rs 70 crore (Rs 700 million). Fifteen years later, this figure had jumped to Rs 3,000 crore (Rs 30 billion) and by the turn of the century, the amount had skyrocketed to Rs 60,000 crore (Rs 600 billion).

In a period of a quarter of a century, the value of the Reliance group's assets had jumped from Rs 33 crore (Rs 330 million) to Rs 30,000 crore (Rs 300 billion).

Using the 'system'

The textile tycoon's meteoric rise was not without its fair share of controversy. In India and in most countries of the world, there exists a close nexus between business and politics.

In the days of the licence-control raj, Dhirubhai more than many of his fellow industrialists understood and appreciated the importance of 'managing the environment,' a euphemism for keeping politicians and bureaucrats happy. He made no secret of the fact that he did not have an ego when it came to paying obeisance before government officials -- be they of the rank of Secretary to the Government of India or a lowly peon.

Long before Dhirubhai entered the scene, Indian politicians were known to curry favour with businessmen -- licences and permits would be farmed out in return for handsome donations during election campaigns.

The crucial difference in the business-politics nexus lay in the fact that by the time the Reliance group's fortunes were on the rise, the Indian economy had become much more competitive. Hence, it was insufficient for those in power to merely promote the interests of a particular business group; competitors had to simultaneously be put down.

Who remembers Swan Mills? Or Kapal Mehra of Orkay? Even Nusli Wadia of Bombay Dyeing is some distance away from where he would certainly have liked to be. The undivided Goenka family that used to control the Indian Express chain of newspapers -- which carried on a campaign against the Reliance group in 1986-1987 -- got broken into three independent sections.

Whereas the multi-edition newspaper has not entirely lost its feisty character, it is yet to fulfill its late founder Ramnath Goenka's cherished dream of becoming a market leader in at least one of its many publishing centres.

The power of Reliance

A popular joke starts with a question: Which is the most powerful political party in India? Answer: The Reliance Party of India. Others divide the country's politicians into two groups: a very large 'R-positive' group and a very small 'R-negative' section.

It is hardly a secret that Dhirubhai's support base would cut easily across political lines. Very few politicians have had the gumption to oppose the Ambanis, just as the overwhelming majority of journalists in the country preferred not to be critical of the Reliance group.

The Indian media, most of the time, has chosen to lap up whatever has been doled out by the group's public relations executives. The bureaucracy too has, by and large, favoured the Ambanis.

While Dhirubhai may not have too many scruples when it came to currying favour with politicians and bureaucrats, what cannot be denied is the fact that perhaps no businessman in India attracted the kind of adulation he did.

He was more than just a legend in his lifetime. He successfully convinced close to four million citizens, most of them belonging to the middle-class, to invest their hard-earned savings in Reliance group companies.

He was fond of describing Reliance shareholders as 'family members' and the group's annual general meetings acquired the atmosphere of large melas attended by hordes.

Can his sons live up to his awesome reputation? Time alone can tell.

The author is Director, School of Convergence and a journalist with over 27 years of experience in various media -- print, radio, Internet and television. He has co-authored a book A Time of Coalitions: Divided We Stand and directed a documentary Idiot Box or Window of Hope.